Much of the press coverage concerning the recent criminal conviction of four former Blackwater security guards in a United States District Court has focused on the difficulty and length of time it took for the case to finally work its way through the judicial system.

Indeed, in the seven years since the incident in Nisour Square, Baghdad left 17 Iraqi civilians dead, the United States has had two Presidential elections, pulled its military (at least until recent weeks) from Iraq, accelerated the drawdown of its involvement in Afghanistan, and introduced new controls on its contracts with private security companies (PSCs). Iraq has changed radically as well, both politically and with regard to day-to-day reality on the ground.

Yet despite the passage of time, reactions to the verdict remind us of why the fundamental issues at trial remain important today. No matter how one evaluates the verdict, private security companies (PSCs) will continue to play an important role in safeguarding government, commercial, and humanitarian interests for the foreseeable future. For that reason, efforts must continue to ensure accountability both by the industry and those whom they serve.

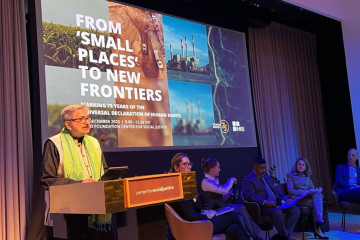

Against this reminder of the past, a significant new initiative to bolster industry standards and accountability is gaining strength. The International Code of Conduct Association (ICoCA) was launched in late 2013 as the governance and oversight mechanism of its namesake Code of Conduct. The Code, developed between 2009 and 2011 through a multi-stakeholder process that was organized and supported by the Swiss government, provides a comprehensive and proscriptive set of expectations for all private security companies operating in parts of the world where the rule of law and/or the capacity of governments to enforce it are weak.

The ICOC provides a comprehensive and proscriptive set of expectations for all private security companies operating in parts of the world where the rule of law and/or the capacity of governments to enforce it are weak.

The Code is grounded in fundamental international human rights and humanitarian law, but was developed as well with a clear eye towards the framework today captured in the U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. It is also more than merely a set of aspirational principles. Rather, the Code and the ICoCA represent a new breed of multi-stakeholder initiative that draws on the lessons and limitations of industry self-regulation and purely voluntary principles to create both a set of expectations and an assurance mechanism in which all stakeholders – industry, civil society organizations (CSOs), governments, and non-state clients – have a role to play in raising performance standards and ensuring accountability to them.

When fully operational, the ICoCA will administer a multi-disciplinary approach to accountability and assurance, incorporating certification of companies, mandatory reporting by companies and monitoring of their performance in the field, and the formation of grievance mechanisms where alleged violations of the Code can be addressed. Each of these processes will be the product of discussions among the stakeholders, taking into account their different perspectives and concerns, but will be executed by an independent oversight body that is responsive to the Association’s Board of Directors (who in turn are equally balanced between the stakeholders). At the same time, the Association will also work towards the establishment of best practices as well as knowledge sharing to enable industry to achieve better performance across the globe. Moreover, the Association has a mandate to assist with the development and harmonization of national and international standards for private security services – whether on land or at sea and whether in the support of governments or private commercial interests.

The ICoCA will not replace the power of sovereign states to regulate industries or to investigate and prosecute violations of their laws. Nor will the ICoCA interfere with these fundamental government functions. Instead, the Association represents a proactive approach to raising standards and performance by directly involving those most affected by performance standards and investing them in their governance. While discussions will no doubt continue concerning national regulations and international treaties, the ICoCA represents the best way forward to achieve improved industry standards today.

In fact, government clients of PSCs are already recognizing the value the ICoCA brings to the field. Switzerland, the United States, the United Kingdom and the U.N. all now require PSCs with whom they contract either to become a member of the ICoCA or to otherwise demonstrate compliance with the substance of the Code. Others will inevitably follow. Private industry clients will also hopefully see the same value and incorporate a similar requirement into their own contracting practices. Doing so would bring substantial benefit to private clients of PSCs, particularly those who have themselves made commitments to respect human rights in their operations.

Presently, over 140 PSCs, 13 civil society organizations, and 6 governments are members of the ICoCA. Acting through the Association’s governance and development structures, these actors have made substantial progress in developing the ICoCA’s assurance mechanisms described above. They have backed up their efforts with substantial financial contributions to ensure that the Association will have the means to accomplish its mandate.

At the same time, the Association is defining a role for and reaching out to non-state clients, like the extractive and major project engineering industries as well as development/aid distribution organizations, to ensure that their needs and concerns are also incorporated into the design and operation of those mechanisms. These stakeholders will play an increasingly important role as the ICoCA’s assurance mechanisms become operational.

There is much to be accomplished yet to ensure that events like the tragedy at Nisour Square are not repeated. To be successful, the ICoCA will continue to require both financial contributions and meaningful commitments from all stakeholders. However, no other effort is anywhere near offering the kind of real impact that the Association is preparing to deliver. And if the Blackwater trial tells us anything at all, it is that efforts to prevent a recurrence of events like Nisour Square will be well worth the price.

How should businesses respond to an age of conflict and uncertainty?

As 2024 began, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen aptly summed up our deeply worrying collective moment. As she put it, speaking at the annual World Economic Forum in Switzerland, we are moving through “an era of conflict and...

26 March 2024 | Commentary

Commentary by Scott Jerbi, Senior Advisor, Policy & Outreach, IHRB