1 IN 20 WORKERS IS A MIGRANT WORKER

There are 169 million migrant workers in the world meaning 1 in 20 workers is a migrant worker.

Migrant workers are a ubiquitous feature of global supply chains and a vital part of the global economy.

The absence of global, regional, or even bilateral policy agreements on the global movement of labour between countries of origin, transit, and employment creates governance gaps that leave migrant workers vulnerable to human rights abuse.

Any business enterprise that uses migrant workers either directly or in extended supply chains must undertake appropriate human rights due diligence to ensure the rights of those workers are respected.

CLICK & DISCOVER

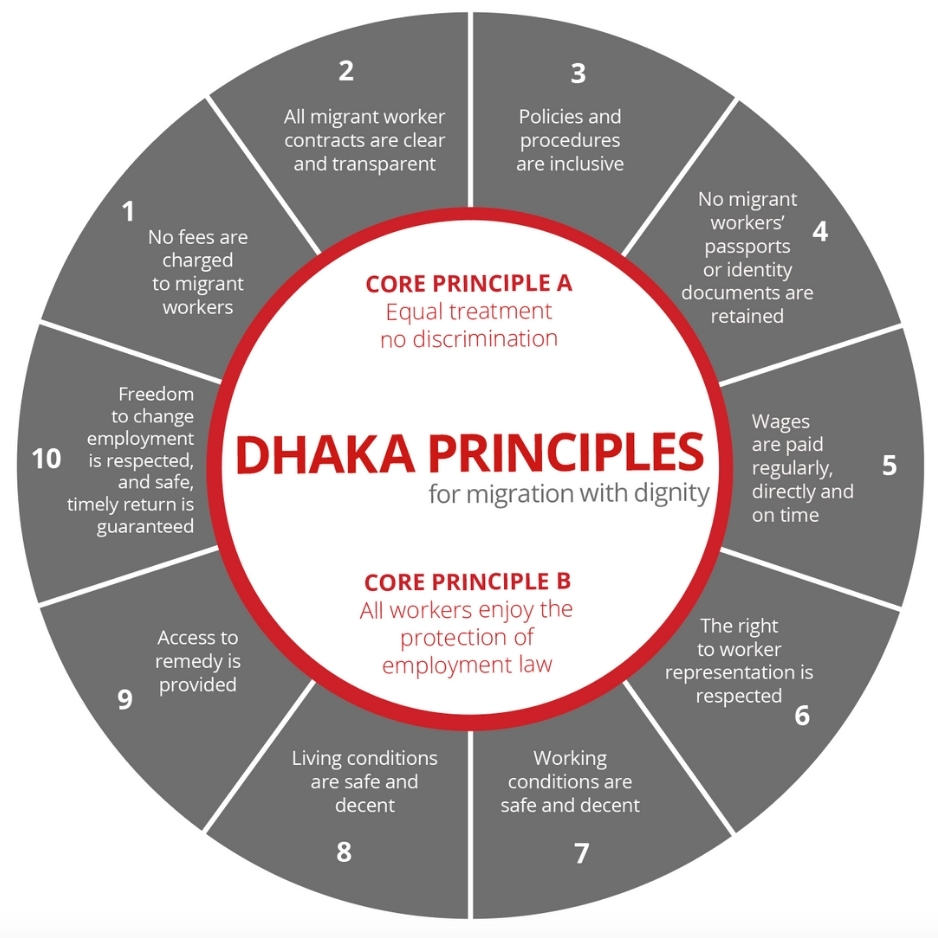

DHAKA PRINCIPLES

for migration with dignityCOMMENTARY SERIES

Discover the Full Series of Commentaries for

10 Years of the Dhaka Principles

To acknowledge the anniversary, throughout 2022, IHRB reflected on each Principle. Guest experts shared their views on progress to date and the challenges remaining for each Principle to become fully realised in the everyday lives of migrant workers around the world.

TRANSLATIONS

The Dhaka Principles are available in a large number of languages. Search your language and download the translation below.

IMPLEMENTATION GUIDE

IHRB has produced produced a detailed Implementation Guide to support companies and other actors implement the Dhaka Principles in their everyday business. Download for additional resources, background information, and guidance.

LinkedIn

LinkedIn Facebook

Facebook Copy Link

Copy Link