What is COP26?

COP26 is the 26th meeting of the Conference of Parties, aka the 26th year that governments, NGOs, trade unions, businesses, and everyone else with any interest in climate change meets to review and negotiate global action. Taking place from 1-12 November 2021 – delayed by one year due to the COVID-19 pandemic - the world headed to Glasgow, Scotland, formally hosted under the UK Presidency.

COP26 is the 26th meeting of the Conference of Parties, aka the 26th year that governments, NGOs, trade unions, businesses, and everyone else with any interest in climate change meets to review and negotiate global action. Taking place from 1-12 November 2021 – delayed by one year due to the COVID-19 pandemic - the world headed to Glasgow, Scotland, formally hosted under the UK Presidency.

Why did COP26 matter? Six years on from the 2015 Paris Agreement, it was a key moment to take stock of progress, but also ramp up commitments alongside a clear plan of action for how climate action targets will be met in the short, medium, and long terms.

Why did COP26 matter? Six years on from the 2015 Paris Agreement, it was a key moment to take stock of progress, but also ramp up commitments alongside a clear plan of action for how climate action targets will be met in the short, medium, and long terms.

- What is the Paris Agreement? Adopted at COP21 in 2015, the majority of the world’s nations committed to containing global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, and preferably to 1.5 degrees. It was a major culmination of more than twenty years of diplomatic action.

- What are NDC's? Nationally Determined Contributions - a timetable agreed in Paris in which each country is expected to submit updated national plans every five years for limiting emissions and adapting to the impacts of climate change. Since 2015, more than 190 countries have published at least one version of their NDC. But NDC ambitions do not yet rise to the level of the Paris Agreement, as the most recent progress report affirms (Sep. 2021).

- And the Paris Rulebook? Countries gave themselves 3 years to agree on the implementation guidelines. At COP24, the UN climate conference in Katowice, Poland, in December 2018, countries adopted the majority of the Paris Rulebook (aka the Katowice Climate Package), consisting of three core tenants: Plan, Implement, Review — but leaving a few unresolved issues (e.g. carbon markets).

- Who's the IPCC? The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – the UN body that issues comprehensive “Assessment Reports” on the state of knowledge on climate change (scientific, technical, socio-economic), the impacts and future risks, as well as options for reducing it.

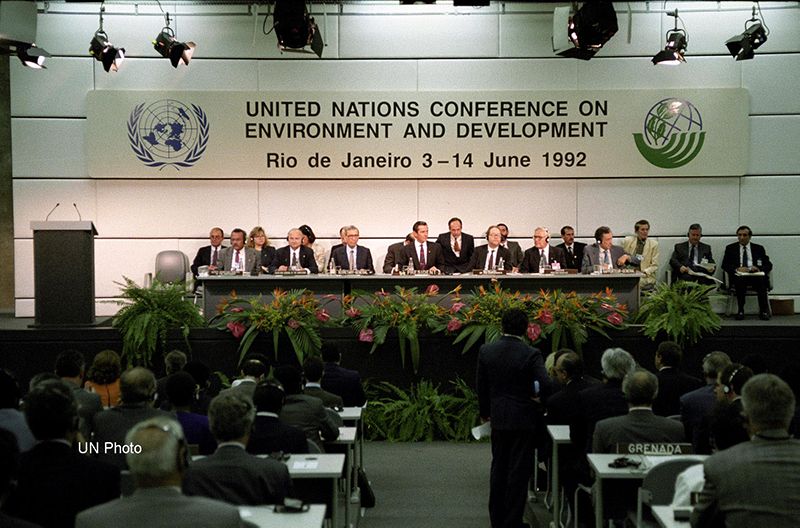

United Nations Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali opening the UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) or Earth Summit - on 3 June 1992. (Flickr/UN Photo)

History of COP:

- 1992: The UN Conference on the Environment and Development (UNCED aka Earth Summit) convening 30,000 representatives of 178 governments, NGOs, media, and other interested in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- 3: Documents that came out of the 1992 Earth Summit - the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (UNCBD), and the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD).

- COP: Conference of Parties - the Governments that signed these legal conventions became “Parties” and started meeting regularly at each “COP” - on climate, on biodiversity, and on desertification. The COP is the supreme decision-making body for each of the Conventions.

- UNFCCC: The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), and its Conference of Parties for signatory governments, is the best known of the COPs, with 197 signatories.

- COP1: The first-ever Climate COP, held in Berlin, in 1995 and annually ever since, now attracting 40,000+ participants from all over the world.

- 2019: Under then-President Donal Trump, the United States quits the Paris Agreement.

- 2021: On his first day in office, President Jo Biden re-joins the Paris Agreement and shortly after releases the USA’s first NDC, setting an emissions reduction target of at least 50% by 2030 compared to 2005 (though this is still higher than the EU’s per capita emissions in 2021).

Who goes to a COP?

- 5 regional groups: African States, Asian States, Eastern European States, Latin American and Caribbean States, and the Western European and Other States – though these don’t really represent the substantive interests of parties.

- Many smaller groupings: National delegations have self-organised into smaller blocs, most notably - Arab States, the Least Developed Countries, the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) group, the G77 group of developing countries, AILAC (Independent Alliance of Latin America and the Caribbean), the EU27 (European Union member states), and the BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, China, India).

- There are also a host of influential non-state observer groups, including:

- ENGOs: Environmental NGOs

- RINGOs: Research and independent NGOs

- LGMAs: Local governments and municipal authorities

- TUNGOs: Trade unions

- YOUNGOs: Youth organisations

- BINGOs: Business and industry

The Youth-led Fridays For Future movement protesting inside COP25. (Flickr/John Englart)

Who organises a COP?

The COP Presidency rotates among the 5 regional groups, as does the COP host and location – a member of one of the 5 regional groups offers to host (“expression of interest”) and the COP adopts a decision (the schedule varies, usually covering a period of 5 years).

The COP Presidency rotates among the 5 regional groups, as does the COP host and location – a member of one of the 5 regional groups offers to host (“expression of interest”) and the COP adopts a decision (the schedule varies, usually covering a period of 5 years).

- UNFCCC Secretariat: The UN body, located in Bonn, Germany, tasked with “supporting the global response to the threats of climate change” – in particular, providing technical expertise in climate negotiations, analysis of information reported by signatories (“Parties”), and maintains the NDC registry.

- Marrakech Partnership: Set up in 2016 to strengthen and accelerate climate action among parties and non-parties to the UNFCCC.

- Climate Action Pathways: Rather than invite its thousands of members to observe the formal negotiations, which are highly exclusive and difficult to follow by even the most diligent of observers, the Pathways platform enables non-UNFCCC parties to "collaboratively shape the vision for a climate-neutral and resilient future".

- Climate Action Champions: There are two that oversee every edition of the COP, appointed by the host countries. They act as a bridge between the Marrakech Partnership and the UNFCCC Secretariat, helping to mobilise action, convene technical expert meetings, and coordinate annual high-level events. The 2021 Champions are Gonzalo Muñoz (Chile) and Nigel Topping (UK).

- Global Climate Action Hub: Among the events the Climate Action Champions help organise every year, held at the COP itself.

What was the COP26 agenda?

The UK Presidency of COP26 has set out 4 main goals for the conference:

- Step up mitigation efforts: Further reduce greenhouse gas emissions in order to keep the 1.5 degree Celsius goal within reach.

- Strengthen adaptation and resilience: Protect the global population, and particularly the most vulnerable regions of the world, from the already unavoidable impacts of climate change.

- Mobilise USD 100 billion in climate finance: Since Paris 2015, developed countries have endeavoured to allocate funding every year to support the decarbonisation of developing countries. This is because the UNFCCC is based on the principle of “common but differentiated responsibility”, i.e. the entire global community needs to take part in the efforts to combat climate change, but those efforts need to be commensurate with the capabilities of each signatory.

- Enhance international collaboration: In particular, finalising the Paris Rulebook.

The UK Presidency has also pointed to 5 themes for COP26 (with little elaborating detail so far) - Clean energy; Adaptation and resilience; Energy transition in transport; Nature-based solutions; Finance

What do human rights have to do with COPs?

“The greatest threat to human rights of the 21st century.” – that’s how IHRB’s founder and Patron Mary Robinson describes climate change. Nearly every human right can be affected by climate change – from water and food, to living standards and migration.

“The greatest threat to human rights of the 21st century.” – that’s how IHRB’s founder and Patron Mary Robinson describes climate change. Nearly every human right can be affected by climate change – from water and food, to living standards and migration.

Here are a few core concepts:

- Substantive human rights: The many different dimensions of a dignified existence that can and will be affected by climate change, such as the rights to life, health, and shelter.

- Procedural human rights: The ways in which the voices of those affected by climate change can be heard, protected through the rights to information and participation.

- Climate Justice: An evolving concept in the context of climate action that is described in different ways to frame climate change as more than a purely environmental issue, often utilising human rights as a key framework.

- Climate Equity: A concept focused on fairness, ie that those who have contributed the least to global warming are often the ones most at risk from the impacts of climate change. In line with the principle of “common but differentiated responsibility”, equity in climate action requires that efforts to mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change should benefit those most at risk, such as people in developing countries, indigenous peoples, people in vulnerable situations and future generations.

- Just Transition: An evolving concept of how governments and business must address impacts on workers and communities as part of moves away from emissions-intensive production (the transition “out”) and into low- or zero-emissions operations, products, and services (the transition “in”).

The extent to which human rights norms and standards are prioritised in national, regional, and international strategies will play a significant role in determining whether the world is on a degenerative or regenerative path in responding to climate change.

20 year old Meenakshi Dewan tends to maintenance work on the solar street lighting in her solar powered village of Tinginaput, India. Meenakshi is one of 4 women who has been trained in solar powered enginneering. (Flickr/DFID)

How Human Rights Should Factor into Corporate Climate Action:

For a deeper dive, check out our report “Just Transitions for All: Business, Human Rights, and Climate Action”, but in brief:

For a deeper dive, check out our report “Just Transitions for All: Business, Human Rights, and Climate Action”, but in brief:

- Prevent, Mitigate, Remediate: The baseline expectation for how businesses should be acting on their human rights responsibilities – and a perfect framework for aligning their climate change due diligence, in particular to ensure their work to transition out of high-emissions and into low-emissions operations, products, and services don’t harm people.

- 6: The main business responsibilities for climate action, according to the UN expert on human rights and the environment – namely:

- reduce GHG emissions from a business’ own activities and their subsidiaries;

- reduce GHG emissions from their products and services;

- minimise GHG emissions from suppliers;

- publicly disclose emissions, climate vulnerability, and risk of stranded assets;

- ensure people affected by the business have access to effective remedies;

- support, and don’t oppose, public policies seeking to address climate change.

- Scope 1, 2, 3: The way that businesses are having to define their GHG emissions (Scope 1 = direct from sources owned/controlled by the company; Scope 2 = indirect from energy that’s purchased; Scope 3 = all other emissions associated with a company’s activities). Scope 3 is especially nebulous and attribution science is still evolving – businesses should not allow the ambiguity that can arise to become an excuse for delayed action.

Climate action requires both ambitious economic transformation and social safeguards so that the costs and benefits of change are shared in an equitable and just manner.

Latest IHRB Publications

Bulldozer Injustice: how a company’s product is being used to violate rights in India

Bulldozers have been linked to human rights violations for many years, at least since 2003 when the US activist Rachel Corrie was crushed to death by a Caterpillar bulldozer while protesting against the demolition of a Palestinian home with a family...

07 March 2024 | Commentary

Commentary by Peter Frankental, Economic Affairs Programme Director, Amnesty International

The state of just transitions in the cocoa sector

The mounting impacts of the climate crisis are seen starkly in the lives of agricultural workers, most often in developing countries. Discussions around just transitions understandably focus on energy, but agriculture and deforestation are also huge...

29 February 2024 | Commentary

Commentary by Tatiana Kurancheva, Commodities Programme, IHRB

08 March 2024 | Video

05 February 2024 | Meeting Report

How should businesses respond to an age of conflict and uncertainty?

As 2024 began, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen aptly summed up our deeply worrying collective moment. As she put it, speaking at the annual World Economic Forum in Switzerland, we are moving through “an era of conflict and...

26 March 2024 | Commentary

Commentary by Scott Jerbi, Senior Advisor, Policy & Outreach, IHRB