Observers of the mining industry, including those who are watching from the inside, have witnessed a growing demand for governments to safeguard people and the environment, and for business leaders to take greater responsibility in the prevention and remediation of mining-induced harms. These harms include environmental contamination, land dispossession, landscape fragmentation, livelihood impacts, and desecration of sacred sites.

The mining industry is operating in a global context where a range of stakeholders exist, with each attempting to influence the industry’s activities.

As academics engaged with the mining industry, we hear the calls frequently from affected communities; sometimes directly and sometimes from advocacy organisations. The industry knows that mining can cause harm, and that its efforts to address the harms to date have been inadequate. This is not a simple case of doing “too little, too late”. Despite objections, protests, and evidence of efforts falling short, the industry is able to operate profitably, and trade on practices that we all know are “too little”. Even so, we are not ready to concede that it is “too late”.

Our new book, Extractive Relations: Countervailing Power and the Global Mining Industry, explains how and why “too little” appears to have worked for the industry for so long, and what can be done to forge a new industrial reality. Decades of lobbying, inquiries, environmental disasters, and persistent claims of abuse all point to the need for industry to do more, not less. Companies find themselves operating in what Professor John Ruggie, former UN Special Representative for Business and Human Rights, has called a “governance gap” – a situation where “too little” passes as acceptable.

Increasingly, industry insiders are agreeing that more must be done.

The mining industry is operating in a global context where a range of stakeholders exist, with each attempting to influence the industry’s activities. These stakeholders include human rights groups, indigenous peoples, gender rights groups, labour organisations, environmental campaigners and so forth. The industry is surrounded by various actors with varying demands exercising their interests and power.

Too many general managers at sites ask why they have to respect the rights of local communities whom they see as ideologues, opportunists, and in some cases as saboteurs.

The Harvard economist and former diplomat John Kenneth Galbraith in his book American Capitalism described modern markets as being characterised by “original power” where powerful corporate actors are able to operate without interference from the state or its citizens. Galbraith argued that “countervailing power” was needed to correct imbalances that the usual market forces had failed to address. In our explanation we see the mining industry as holding original power and the other stakeholders we've described above as wielding varying degrees of countervailing power.

The explanation, we acknowledge, isn't an immediate fit.

To begin with, the industry does not see itself as a powerful actor. Instead, companies depict themselves as being under attack from lobbyists, critics, local communities, and occasionally governments. Most global mining companies are familiar with and have taken steps that are consistent with global safeguard instruments like the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, and the IFC Performance Standards. These safeguard instruments carry little sway at mine sites (where the action happens). Too many general managers at sites ask why they have to respect the rights of local communities whom they see as ideologues, opportunists, and in some cases as saboteurs.

Where companies are vulnerable, there are opportunities for other social actors to disrupt or impede mining operations.

While the countervailing power exists, we have observed that it appears to be ineffective in breaking up the “original power” of mining companies. As it turns out, the use of “countervailing power” by communities invites companies to assert yet more of its “original power”. Sometimes that can have catastrophic consequences, such as when security protecting mine sites use disproportionate force against communities which may be protesting peacefully, creating a human rights crisis.

We know that the time, effort, and resources that communities spend engaging mining companies is rarely acknowledged by the sector.

We call this a “trading of powers”. What concerns us most about this trade is the transaction costs for communities. When people speak out against a project, or engage in public protest, for example, they may be putting themselves at risk of harm or abuse. We know that the time, effort, and resources that communities spend engaging mining companies is rarely acknowledged by the sector. Host communities do not have the same power or resources that mining companies possess. Preventing or impeding mining operations is one of the few options available to communities when companies cannot see or will not take responsibility for the harms caused by the mine.

Industry-wide we see little change in the way that companies run their business.

The practice of “too little”, supplemented with the occasional exercising of original power, is effective and profitable for many companies. The externalised cost of holding companies to their commitments is not sustainable for host communities and governments, and it does not reflect what the industry has signed up for internationally. There is a pressing need for change.

Shared local authority means conceding original power, at the asset level, where it counts most.

In Extractive Relations we argue that for countervailing power to be effective in moderating this industry, communities must be engaged in meaningful ways.

Sharing authority over project decisions is one means of addressing power imbalances. This goes beyond “good neighbour agreements” and would mark a major departure from current thinking and practice. Shared local authority means conceding original power, at the asset level, where it counts most.

For this proposal to succeed, we argue that companies need to internalise the social battle and shoulder the costs.

A new corporate architecture is suggested as an alternative to companies and communities continuing to “trade powers”. The industry needs to begin hardwiring social functions into its core business activities, if its many governance gaps have any chance of being filled.

How should businesses respond to an age of conflict and uncertainty?

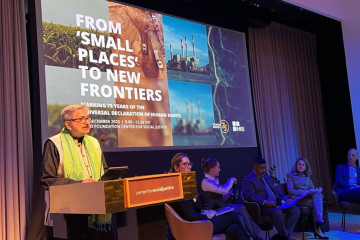

As 2024 began, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen aptly summed up our deeply worrying collective moment. As she put it, speaking at the annual World Economic Forum in Switzerland, we are moving through “an era of conflict and...

26 March 2024 | Commentary

Commentary by Scott Jerbi, Senior Advisor, Policy & Outreach, IHRB