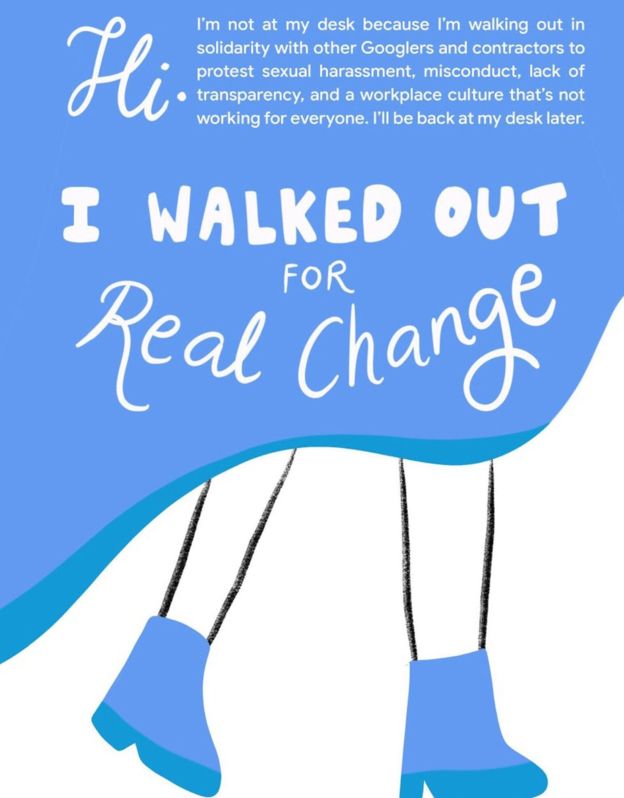

On 1st November 2018, some 17,000 Google employees in more than 40 offices across the world left identical notes on their desks, saying “I’m not at my desk because I’m walking out with other Googlers and contractors to protest sexual harassment, misconduct, lack of transparency, and a workplace culture that’s not working for everyone.”

Companies that say they uphold universal values will face serious scrutiny from their own staff, who will challenge senior executives and ask the company to live up to their commitments.

The mass walkout by some of the best paid and skilled people in any corporation highlights four important developments concerning the hi-tech sector. One, that no business, not even the well-paid, individualistic and innovative hi-tech sector, is immune from sexual harassment. Two, emboldened employees will raise their voice, even when they are not unionised and have not felt the need to organise themselves in the past. Three, the tech sector has a gender problem that it must address and take urgent steps to change – saying it is meritocratic simply won’t do. And four, companies that say they uphold universal values will face serious scrutiny from their own staff, who will challenge senior executives and ask the company to live up to their commitments, and that is a good thing.

Emboldened employees will raise their voice, even when they are not unionised and have not felt the need to organise themselves in the past.

The immediate provocation for the Google protest was a New York Times story, which revealed that the company had paid Andy Rubin, a departing executive, $90 million as severance while not disclosing a serious claim of misconduct against him when he left in 2014. The internal backlash was immediate, and Google’s chief executive Sundar Pichai and co-founder Larry Page took immediate steps to reassure the company’s workforce that sexual harassment would not be tolerated. Forty-eight employees had been let go over similar charges in the past two years, Pichai added, and those who left since 2016 under such circumstances had not received any payout. He supported the employee activism, admitting that the Times story was “difficult to read”, and reassured his staff in an email, saying, “I understand the anger and disappointment that many of you feel. I feel it as well, and I am fully committed to making progress on an issue that has persisted for far too long in our society… and, yes, here at Google, too.”

But Google employees wanted to demonstrate their outrage, and at meetings in cities across the world, they said this action was the beginning, not the end.

Their six demands were:

- A commitment to end pay and opportunity inequality;

- A publicly disclosed sexual harassment transparency report;

- A clear, uniform, globally inclusive process for reporting sexual misconduct safely and anonymously;

- The elevation of the chief diversity officer to answer directly to the CEO, and make recommendations directly to the board of directors;

- The appointment of an employee representative to the board;

- An end to forced arbitration in cases of harassment and discrimination for all current and future employees.

With its outwardly egalitarian and meritocratic structure and a focus on creativity and innovation, the hi-tech sector conjures the impression that every employee has an equal opportunity to succeed and those who reach the top are there strictly on merit. Given the industry’s reliance on private capital whose primary aim is to make profit, it is not an unreasonable assumption to make. But each organisation mirrors the society in which it operates.

Many, including engineers, still believe women are not good at tech jobs.

The tech sector in the United States is disproportionately lopsided, with more men who are white (and some Asians) in senior positions, and few women, or people of colour, reaching the upper echelons. A new book by Joy Lisi Rankin argues that the predominantly white and male culture in the computing industry owes its origins to the atmosphere prevalent at Dartmouth College in the United States, where engineering professors and mathematicians developed an early computing language, called the Beginners’ All-Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code (BASIC) in the 1960s. Dartmouth didn’t admit women as students at that time, so the small, rural campus in New England developed a ‘frat boy’ reputation, and its early success led this to be recreated at other campuses, including at companies. Whether or not the roots of such behaviour lie in rural New England, many, including engineers, still believe women are not good at tech jobs.

Last year a Google employee was fired after he wrote an internal memo in which he claimed that women were biologically unable to be effective engineers. (Personally, I find the assertion to be just that – an assertion: my late wife was an engineer in the tech industry, and although she would agree that there were few women engineers, it was certainly not because ‘women couldn’t do math’.) The former employee, James Damore, bemoaned what he described as the politically correct ideological echo chamber that did not allow contrarian ideas to be expressed. He contended that the company’s focus on diversity would in the long run erode its competitiveness.

Many scientists disagreed with Damore’s assertions. Indeed, at the annual meeting of Alphabet (Google’s parent company) employees asked for executive compensation to be tied to managerial performance on improving diversity metrics. (Only 19% of Google’s tech workforce is female; at Apple, female workforce in tech jobs is 23%, and at Facebook, 17%). This has partly to do with fewer women engineers, and to address that, companies including Facebook, and beyond the tech sector, GE and ExxonMobil, provide support, including grants and scholarships, to girls to study science and math at high school and later.

Amazon scrapped a recruiting tool based on artificial intelligence it had developed after it found that the model was biased against women.

The problem of sexism in tech is real. British science writer Angela Saini, in her recent book, Inferior: How Science Got Women Wrong and the New Research That’s Rewriting the Story, shows the implicit bias in-built and hard-wired into our thinking, which makes people accept as ‘fact’ that women are not good at science or technology. She explains the real differences in how men and women think and feel, and examines how science has excluded women since the Enlightenment and the prevailing neurosexism in scientific research at present, revealing our flawed thinking.

To be sure, Google is not the worst offender. Last year, Susan Fowler, a former engineer at Uber, the ride-hailing company, wrote a blog about her ‘very strange year’ at the company, about her manager making sexual advances towards her almost from the day she started work. It blew into a major crisis at the company. Other examples of biases abound: Amazon scrapped a recruiting tool based on artificial intelligence it had developed after it found that the model was biased against women.

The 2016 Women in the Workplace study showed that only 19% of the tech sector's top executives are women.

Such biases feed discriminatory attitudes. Ellen Pao failed in her lawsuit against Kleiner Perkins Caufield and Byers, a venture capital firm, over sexual harassment and discrimination, but she forced rethinking among some senior executives in the Silicon Valley because a dissatisfied workforce would mean lower morale, which would affect creativity and productivity.

Demeaning the role and contribution of women has other consequences. The 2016 Women in the Workplace study showed that only 19% of the tech sector's top executives are women. Some 84% of the women in the sector were told they were being aggressive or bossy, even if they made simple demands such as equal pay. A Tinder executive, Whitney Wolf, sued the company because she was verbally abused often by a senior executive and denied the title of ‘co-founder’. Tom Preston Werner, the founder of a coding site, GitHub, resigned after a sexual harassment investigation.

Two out of five women in corporate America say they have been harassed.

Sexual harassment is of course found in every industry – two out of five women in corporate America say they have been harassed – but Silicon Valley trumps that statistic, with a survey, called The Elephant in the Valley, showing that 60% of women in the tech sector have faced sexual harassment. The survey also found that 87% of the 220 women interviewed had witnessed demeaning comments from their colleagues. Almost 40% of those who said they were harassed at work did not report the situation, fearing it would damage their careers. Given that women form a small proportion of the total workforce, that’s alarming.

The Google walkout shows that companies will increasingly face calls for collective bargaining.

There is a larger consequence of activism at Google. The tech sector largely frowns upon trade unions, believing that unions are unnecessary in a sector where those with requisite skills are paid premium dollars, and if someone is dissatisfied with the terms, she can simply take her laptop and move to another job. The Google walkout shows that companies will increasingly face calls for collective bargaining. Among the Google employees’ demands is a seat on the board for workers’ representatives. This is straight out of trade union politics.

Experts believe that other companies – such as Facebook – are watching what happens at Google with apprehension and anxiety. For example companies like Microsoft, which may be bidding for contracts with the US immigration services which is cracking down on immigration are facing protests internally to drop ICE contracts.

Indeed, Google employees have been vocal in recent months about issues that matter to them. They challenged the company to not bid for a cloud computing contract that was worth $10 billion with the US Department of Defense, as it would have violated Google’s own principles on artificial intelligence. They have protested the company’s work on a secret search engine for use in China. Some employees have quit the company over this project. Google had been widely praised for not entering the Chinese market over censorship concerns, and the fact that it was considering re-entering the market was enough provocation for many within the company to protest. “Don’t be evil,” is the company’s motto – its own employees are holding the company to that standard.

“This doesn’t end today,” one Google employee said. She is right. While Google is not perfect, it aims to make its workplace inclusive and diverse, seeing financial advantages as well as benefits that can’t be measured in monetary terms. Its motto – don’t be evil – may sound New Ageish to some, but taken literally, it means preventing and undoing harm. That’s a very good place from which to start for any company that wants to take human rights seriously.

[Google's] motto – don’t be evil – ...means preventing and undoing harm. That’s a very good place from which to start.

Google should be applauded for listening to its employees. It has already accepted one of the demands – of forced arbitration: it will no longer be forced, leaving the employee the option to use courts. The harder part is taking steps to reduce harms already caused, and preventing them from recurring. Its employees, and many others, will be watching.

How should businesses respond to an age of conflict and uncertainty?

As 2024 began, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen aptly summed up our deeply worrying collective moment. As she put it, speaking at the annual World Economic Forum in Switzerland, we are moving through “an era of conflict and...

26 March 2024 | Commentary

Commentary by Scott Jerbi, Senior Advisor, Policy & Outreach, IHRB