What is community ownership for renewable energy?

13 December 2022

What is community ownership?

Community ownership is an ownership model for energy projects where the assets are jointly owned, operated, and controlled by members of a community and the project developers/operators. It is especially suitable for Indigenous and non-indigenous communities, schools, and municipalities. The model enables communities to participate in decision-making affecting the governance, operational management, and maintenance of renewable energy projects and reap the rewards, including self-sufficiency, wealth, and the aspirations of the local community.

Even though projects owned by communities are usually modest due to financial constraints, community ownership is considered one of the most promising ownership models to ensure a just transition. In the context of Indigenous rights, a community ownership approach recognizes Indigenous rights and sovereignty to control and manage ancestral and traditional lands, waters and other natural resources.

How does community ownership work?

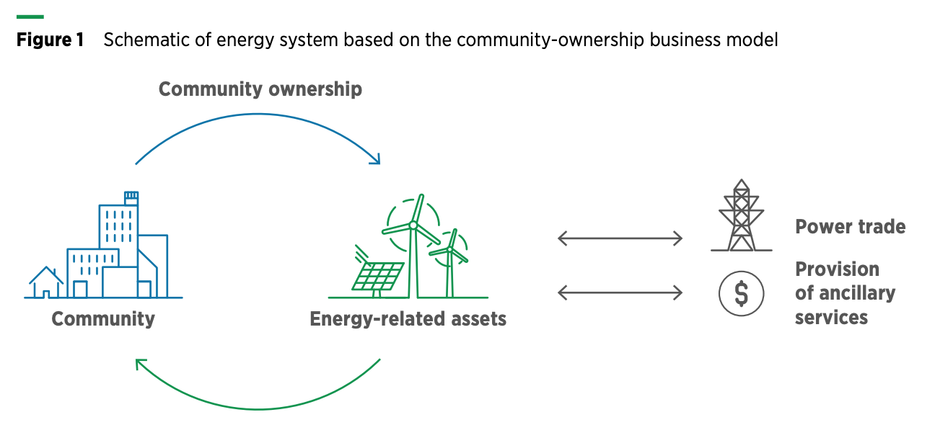

In a typical community ownership model, the community owns, operates, and reaps the benefits from the project, with the energy developer playing a supporting role. Depending on the legal structure, type of ownership, distribution of profits, and degree of democratic governance, the execution of the community ownership model can take numerous shapes. The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) states that a community ownership model incorporates two or more of the following components:

- Ownership structure: in the strongest version of the community-ownership model, the community has full ownership of the energy development. In other instances, the community may have majority ownership, while other stakeholders, such as traditional energy developers, participate as partners. The third alternative is that energy projects can be driven by energy developers, with communities acquiring a minority ownership stake in the project.

- Level of democratic governance: a community organisation or a co-operative has voting authority in any decision-making concerning the renewable energy project.

- Local distribution of profits: the communities reap most of the social and economic advantages, such as jobs, energy supply, and financial returns.

Why is community ownership in renewable energy beneficial?

There are numerous benefits to community-owned renewable energy projects:

- Communities gain economically, socially, environmentally, and financially from projects constructed on their lands. The economic benefits flow directly back to the local community while reducing their carbon footprint and generating renewable energy.

- Cost-sharing is enabled with the community-ownership model, reducing up-front expenditures and allowing for a decentralised renewable power source.

- It increases communities' energy access, security, and independence. Additionally, it generates new employment and empowers communities by fostering a sense of pride.

- The community-ownership approach reduces community resistance to renewable energy projects, hastening the energy transition in a fair and just way. Local communities are more likely to ensure that projects are done in a way that is least damaging to local environments and ecosystems. As noted by a First Nations Chief involved in the Pukis Community Wind Park (see below), the project was important in “ensuring we limit our impact on the environment and natural resources”.

- It builds and enhances the capacity and skills of local people in areas such as project management, communications and governance.

Where have community-ownership models been implemented?

There are numerous examples of successful community-owned renewable energy projects:

- Hepburn Community Wind Farm: A 4.2 MW wind farm in Australia where local residents have majority ownership. Over 2000 community investors raised $9.8 million for the project. The wind farm contributes over $30,000+ a year to a local Community Sustainability Fund.

- Minwind I-IX: A set of wind farms in Minnesota, USA which are operated by nine corporations but 100% owned by 33 different local farmer-investors. The project cost $16.5 million in total, funded by selling shares and debt. The project also received a 10% funding grant from the US government.

- Pukis Community Wind Park: This wind park situated north of Toronto, Canada is a co-operative between the Windfall Ecology Centre and the Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation. The shareholders include First Nation peoples and others from the Toronto area. Not only do the Chippewas have direct influence on reducing the wind farm’s impact on the land and ecosystems, the project also provides income and employment.

What are some challenges and best practices in the community-ownership model?

The adoption of the community-ownership model in renewable energy projects can face a number of challenges:

- Community ownership models call for policy frameworks that need to be customised for differing local contexts.

- The administrative procedures involved in the development of energy projects, including planning, licensing, building permits, and environmental impact analyses, are intricate. This is particularly the case in co-operative arrangements where there may be additional regulatory requirements and challenges around who is responsible for the project.

- As energy projects often demand significant up-front expenses, it could be challenging for communities to access capital and find advantageous financing arrangements.

- Access to a power grid and long-term power purchasing agreements at a fair price are also challenges to the financial viability of community-owned projects.

- Lastly, there is a gap in resources to increase community capacity and access to knowledge and technical know-how required to create energy initiatives.

These challenges can be solved, and some of the best practices include:

- Government support in the form of grants, loans, microcredit, tax incentives and subsidies. In the Hepburn Community Wind Farm (mentioned above), support provided by the state government of Victoria was critical to giving community investors greater confidence in the project.

- Government policies around grid access and fair tariffs can also allow community-ownership models to benefit. It was when Ontario introduced the Green Energy Act that projects like Pukwis could become financially viable through stable tariffs and 20 year power purchase agreements at a set price.

- The costs of a project can also be driven down through collective bargaining. In the Minwind I-IX project, the farmers collectively negotiated with all the Minwind projects to secure a fair price with a utility company in the power purchase agreement.

- The procedures and regulations around energy project development should be simplified and accessible to facilitate community ownership.

- Appropriate partners should be identified both for funding as well as professional and project management expertise. Working together with local developers can help close funding shortages and improve creditworthiness.

- The gaps in capacity and skills within communities may be addressed by launching training programs and linking communities with specialists and other communities that have carried out similar projects.

What is the relevance to business and human rights?

The human rights risks of renewable energy projects for local communities include land or ocean grabs, a breach of the right to free, prior and informed consent for Indigenous peoples, the loss of traditional livelihoods, disruptions to Indigenous culture and identity, the destruction of important ecosystems, conflict and violence against those defending their lands and many others.

The community ownership model can be an important tool to ensure a just transition to a net-zero economy and to protect and benefit Indigenous communities. Communities' resistance to building renewable energy facilities on their property can be diminished by actively incorporating them into energy projects, ultimately speeding up the energy transition, assuming all appropriate consultation and negotiation has taken place.

Most importantly, a community-ownership model prioritises the autonomy of the local community in decision-making processes throughout the lifetime of the project. This is critical to upholding Indigenous rights to self-determination and to free, prior and informed consent (consistent with the principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Other IHRB resources:

- COP27 Dialogue on Business, Human Rights, and Climate Action across the Wind Energy Sector November 10, 2022

- A Just Transition for Communities: Can Wind and Solar Projects Turn Human Rights Lessons into Leadership? August 09, 2022

- Harnessing Coastal Wind Energy Responsibly: Community Rights and Benefits August 08, 2022