What is the Crew Change Crisis?

27 July 2021

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, many hundreds of thousands of seafarers – i.e. merchant crew who work on cargo ships – have been ‘stuck’ on board their vessels - unable to disembark and go home at the end of their contracts. An equivalent number are unable to board ships to work. At its peak it is estimated that up to 400,000 seafarers were unable to be repatriated. Estimates for May 2021 put the figure at 200,000. (Latest figures can be found via the Neptune Declaration crew change indicator.)

What is the background?

90% of world trade is conducted by sea – raw materials (e.g. oil, lumber, soybeans), and finished goods (e.g. trainers, mobile phones, cars) – are all transported via cargo ships that travel across the globe, often stopping at many ports to on- and off-load goods. These ships are collectively manned by a global crew of approximately 1.6 million seafarers who are employed on contracts by ship owners, operators, managers, charterers and others. The majority (51%) are from China, Philippines, Indonesia, Russia, India, and Ukraine.

Why is it happening?

Since the COVID-19 pandemic started, many countries, in order to prevent the coronavirus being spread among their populations, have closed or restricted some or all ports and airports to foreign nationals, including seafarers. The result is that although ships are able to offload goods, crew may have to remain aboard until the ship reaches a port that allows crew repatriation and replacement, leaving those seafarers obliged to continue working, sometimes beyond their contract durations. ILO’s 2006 Maritime Labour Convention (MLC) states that the maximum continuous period that a seafarer should serve on board a vessel without leave is 11 months - the average actual duration of seafarers’ contracts varies, but is typically between three and nine months (followed by unpaid time ashore).

Lauro De Guzman Jr. | "Connected"

Connecting at home is the most important thing for a seafarer now. In this new life of pandemic, where seafarers don't know when or how they are coming back home while thinking everyday how the lives of their families will put everything only into hope and prayers. Knowing that your family is okay during these hard times makes our heart calm like [the] sea. So stay strong, stay connected and stay still. I am still at sea while my heart is at home.

Why is it a human rights issue?

Regular crew changes are essential to comply with international maritime regulations for safety, crew health and welfare, and employment. When at sea, crew may work 10-12 hours shifts, up to seven days a week – working at this pace and intensity for extended periods of time threatens the safety and wellbeing of crew as well as the safe operation of maritime trade more generally.

Seafarers stranded on board ships have expressed exhaustion, fatigue, anxiety and mental stress, and their situation is exacerbated by lack of certainty about when they may be able to go home. With some seafarers reportedly trapped aboard their vessels for over a year or more beyond their contracts, the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF), has stated that the crew change crisis amounts to “a serious violation of fundamental human and labour rights.” The International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations stated in December 2020 that the crisis is increasingly resulting in ‘situations which could amount to forced labour’. IHRB has highlighted the crew change crisis as one of the top ten most critical business and human rights issues that need urgent attention in 2021.

What are the challenges involved in resolving the crisis?

There can be considerable cost implications of arranging crew change as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. These include: arranging alternative charter transport, sorting visa issues, flights via multiple ports, and the possibility of ships having to deviate from their courses by many miles to ports that allow crew to change and the resulting impact on fuel use, cargo delivery, amongst others.

Ruflyn Balili | Single Mother on Board

Photo taken last August 19, 2020 It was his 4th birthday and again, I wasn't there to celebrate with him. Luckily I ask[ed] my supervisor if I can go late just to spend time with him through Zoom. Being far from my son is a big sacrifice for me as a mother but I need [to] work hard for him and for my family too.

What are governments doing?

It is primarily a matter for states to ensure implementation of the Maritime Labour Convention and to put in place processes that will facilitate crew change through their ports of entry and exit.

The UN Secretary General and UN agencies have called on governments to designate seafarers as “key workers”, to honour their commitment to seafarers (especially as it relates to medical care, length of service and repatriation), and to adopt the International Maritime Organization’s Recommended Framework of Protocols for Ensuring Safe Ship Crew Changes. (See for example resolutions by UN General Assembly, IMO Maritime Safety Committee, the ILO Governing Body, and the ILO’s Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations.)

Governments must classify seafarers as key workers and prioritise seafarers for vaccination.

Happy Augustinus Manuel Rumondor | Sun bathing and doing fishing

During [the] Pandemic – could not repatriate. We are doing daily sun bathing – [we] believe it to increase body immunity. And of course I did my hobby, fishing.

What about businesses?

Numerous organisations, IHRB among them, are advocating for businesses to play their part in addressing and alleviating the crisis. Under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, businesses have a responsibility to respect worker rights. Businesses engaged with the maritime industry (either directly or through their business relationships) can use their leverage – individually and collectively - to ensure respect of seafarers’ rights, and should not exert undue pressure on the maritime industry (e.g. through no crew change clauses – that is, no crew changes can occur whilst the charterers’ cargo is aboard – or restrictions on deviation) to lessen the protection afforded by existing standards. For a step by step guide to actions cargo owners and charterers who use maritime transport can take, companies should refer to the UN Global Compact's Maritime Human Rights Risks and the COVID-19 Crew Change Crisis: A Tool to Support Human Rights Due Diligence.

Learn more about the Crew Change Crisis

Podcasts

- Francesca Mangano (TFG London) on Addressing the Crew Change Crisis (May 2021)

- Kate Pike on the Mental Health of Stranded Seafarers (Feb. 2021)

- Jacqueline Smith (ITF) on the 300,000 Seafarers Stranded at Sea (Sept. 2020)

Commentary

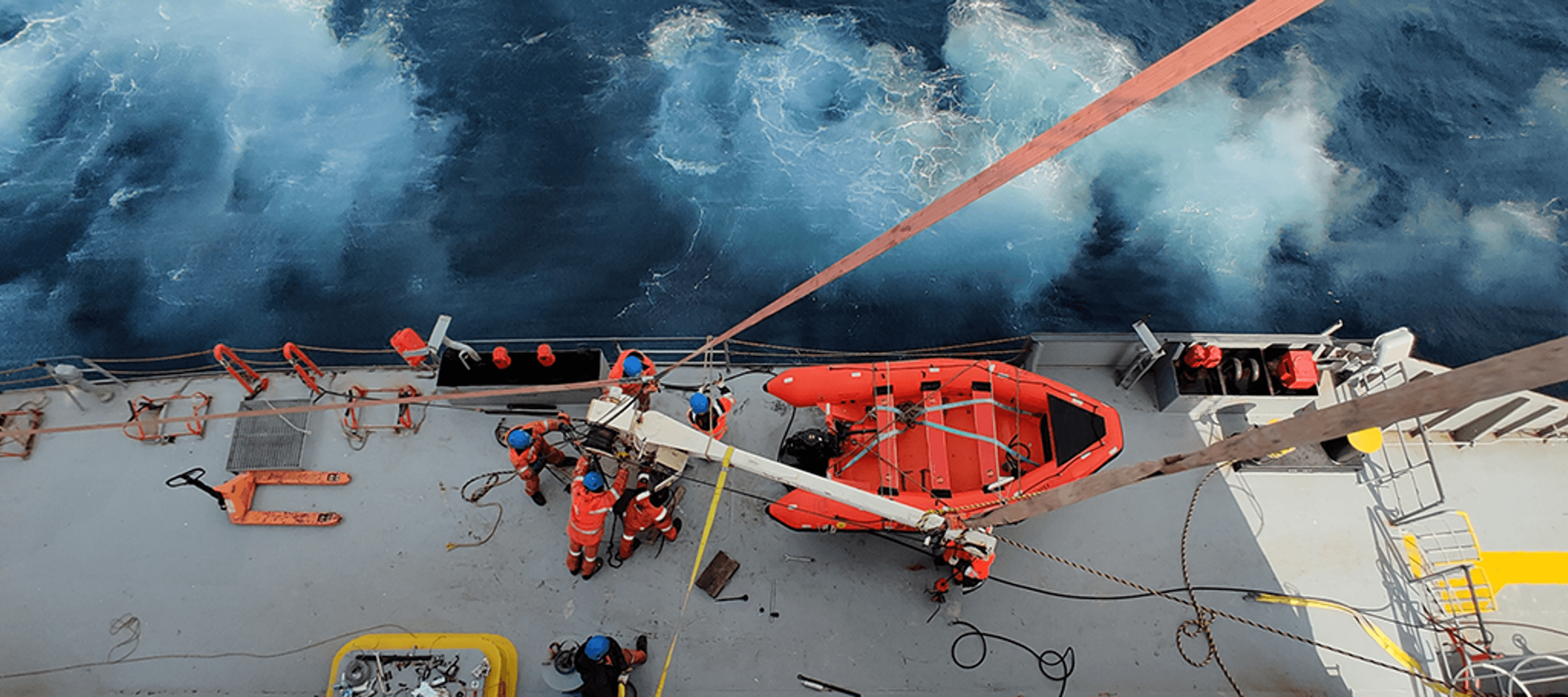

- In Pictures: What It’s Like to be a Seafarer During a Pandemic (Feb. 2021)

- The Invisible Transport Workforce Keeping Supply Chains Moving (Mar. 2020)

Top Ten Issues

More about IHRB's Maritime Programme

Guidance and dialogue

- IHRB: Human Rights and the Ship Lifecycle - From Shipyard to Scrapyard (2019)

- IHRB/Rafto/DIHR: The Responsible Shipping Dialogue (ongoing)

- IHRB/SSI: Human Rights Code of Conduct for Charterers (forthcoming)

Podcasts