Realising Rights and Maximising Benefits: improving development outcomes through the responsible recruitment of migrant workers

16 May 2022

Executive summary

In 2021, IHRB commissioned an independent study to examine the nexus between employment abroad and development outcomes, focusing in particular on lost economic and social benefits linked to migrant workers being charged recruitment fees and related costs. The full report by Maria Vincenza Desiderio provides detailed analysis and views on this issue and the steps needed to address current challenges.

This short paper highlights some of those key findings and offers recommendations for governments, business, and the recruitment industry on how to improve recruitment practices that would safeguard the rights of migrant workers whilst maximising the development potential of their work abroad.

In a global economy, little is undertaken which has not included input from a migrant worker somewhere. Large scale recruitment of migrant workers is a significant feature of a number of economies in Southeast Asia such as Malaysia, Thailand and Taiwan. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, Singapore and Hong Kong are also dependent on foreign workers across a range of sectors. Workers from Central America and the Caribbean are similarly employed in the USA and Canada.

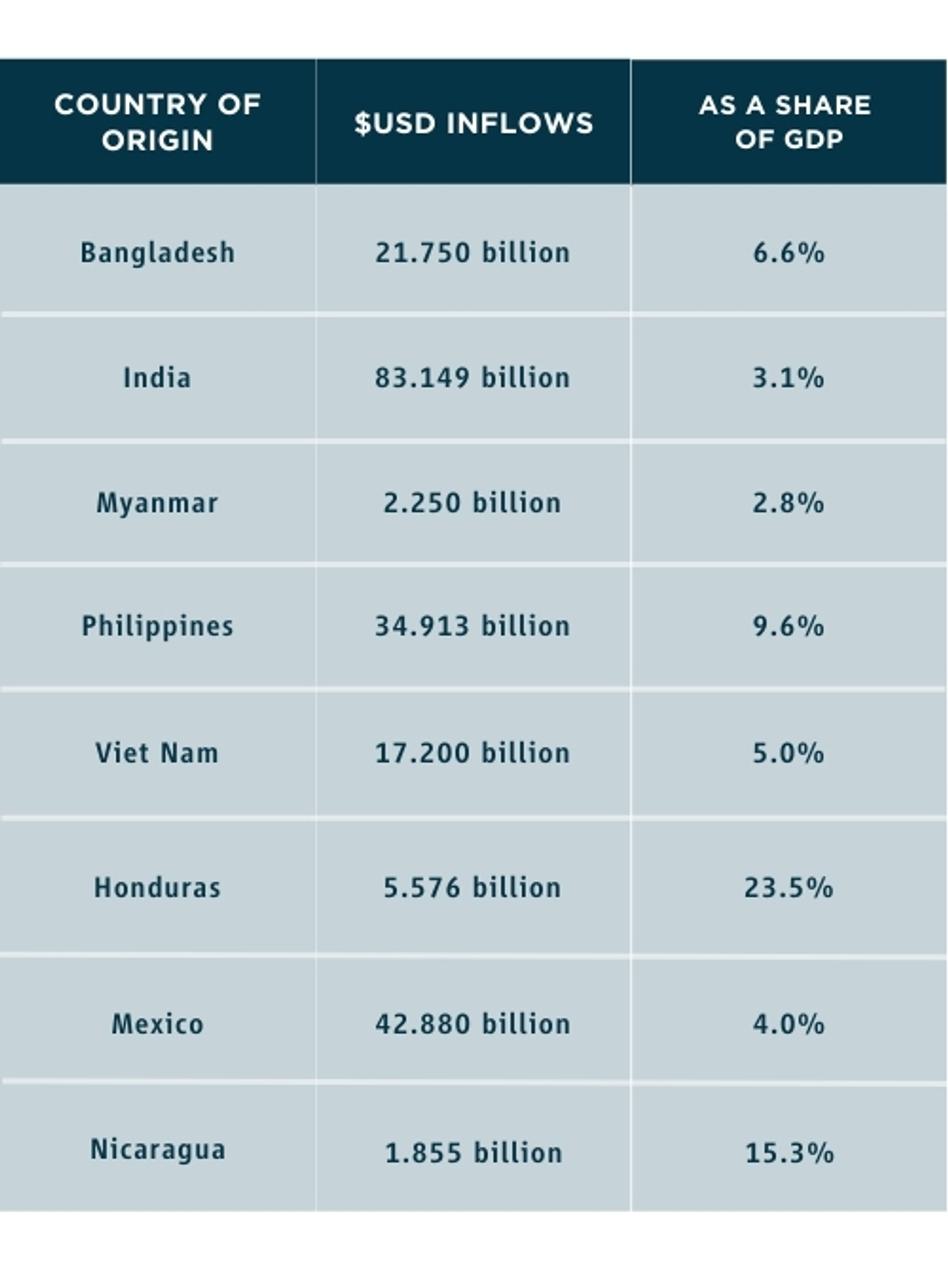

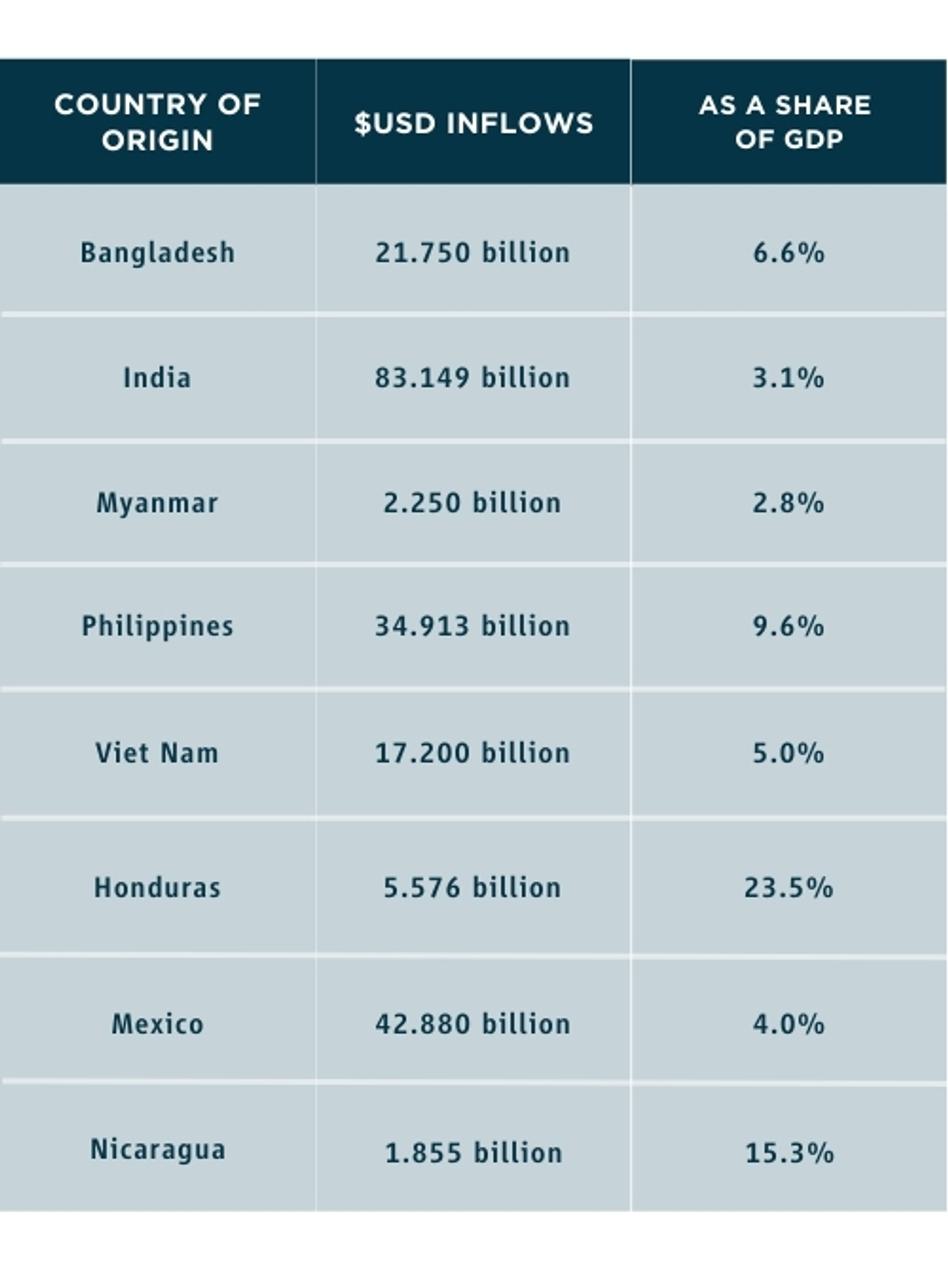

The important role migrant workers play in the global economy can be seen in flows of money migrant workers send from countries of destination to countries of origin (remittances). For instance, in 2020, USD $34.5 billion was remitted by workers employed in Saudi Arabia. Similarly, in the same year, Bangladesh received $21.75 billion (6.6 % of its GDP) from workers abroad. Migrant remittances, often sent to some of the most financially challenged countries and communities, have the potential to help deliver a range of development benefits. In 2021 total remittances to low- and middle-income countries were projected to be $589 billion – three times the amount received globally in Official Development Assistance (ODA).

The Impacts of Recruitment Fees on Global Remittances

The value of migrant worker contributions to countries of both origin and destination is greatly eroded by a range of fees commonly charged to migrant workers. These fees form part of a ubiquitous business model that fails to respect the rights of migrants and persists due to government shortcomings in legislation and enforcement.

Flawed recruitment processes are a major contributory factor in migrant workers’ exploitation, with many migrant jobseekers paying large recruitment fees to secure employment abroad. This iniquitous practice leaves many in situations of debt bondage and vulnerable to further exploitation. The costs charged to workers often go far beyond the genuine costs of recruitment and deployment and in some cases may total the equivalent of up to 24 months salary. To afford these charges, many workers take out loans against the promise of future earnings. The ensuing recruitment debt sits with them, often throughout their time abroad, particularly if the earning potential of the position falls short of the recruiters’ promises.

The practice of migrants paying recruitment costs is deeply embedded and entrenched within some of the major recruitment corridors. An oversupply of recruitment agencies, combined with large numbers of potential migrants desperate for a job abroad, has created intense competition amongst agencies weakening their bargaining position with hiring managers abroad. In some situations, hiring managers or recruiters in countries of destination will expect payments for job offers. Recruiters in countries of origin will often add these costs to the fees they are charging workers.

The issue of recruitment fees charged to workers has become a key part of government and business strategies to prevent forced labour for instance through denying access to markets for goods produced by workers who have paid fees. Less acknowledged is the adverse impact recruitment fees charged to workers have on development outcomes - despite the significant importance of this issue to broader policy objectives.

Alignment with Government Duties and Broader Commitments to Sustainable Development

Governments at both ends of the recruitment corridor should see the advantages in protecting migrant workers during recruitment. For countries of destination, flawed recruitment processes that exploit workers may mean inefficiency and contribute to poor productivity. It may also bring additional international scrutiny and economic or other sanctions. For countries of origin, it can erode economic remittances and limit the acquisition of “social capital,” the circulation of knowledge, ideas, practices and skills, between sending and receiving communities.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and associated Sustainable Development Goals adopted by all UN Member States in 2015 provides a blueprint for action on a range of targets to reduce poverty and inequality, protect health and wellbeing, whilst safeguarding the planet. Protection for migrants is acknowledged in SDG 10.7: “Facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people, including through the implementation of planned and well-managed migration policies”

To date, many approaches to tackling the issue of recruitment fees being paid by migrant workers have focussed exclusively on prevention of forced labour. Although this is a critical issue, it does not address the full implications of current practices in perpetuating the supply of people vulnerable to exploitation. Using a development lens to review and challenge existing models of migrant worker recruitment could see governments enacting more effective legislation and strengthening law enforcement and labour migration governance. Through tangible actions on recruitment in their operations business too can demonstrate their commitments to the Sustainable Development Goals.

Recommendations

Establishing the safe and ethical systems for recruitment that are needed requires Governments and business to first recognise the rights of migrant workers. A critical element in any strategy is the adoption of new models of recruitment where recruitment costs and charges are recognised as a business cost and paid by business. The growing commitment to the Employer Pays Principle: No worker should pay for a job. The costs of recruitment should be borne not by the worker but by the employer, is one important step in ensuring better protection for all workers, a level playing field for law respecting business and better outcomes for developing economies.

The following recommendations would deliver clear migration pathways that are safe, efficient and that would realise the rights of migrant workers whilst maximising the socio-economic benefits of migrating for work.

For Governments:

- Governments should ensure clear, transparent, and accessible processes for trans-national recruitment.

- Governments should develop robust, transparent, and publicly available licensing systems for recruitment agencies.

- Bilateral agreements between governments should include clear and binding prohibitions on charging recruitment fees and costs to workers in both countries of origin and destination.

For Business:

- Companies should commit to the Employer Pays Principle and ensure that workers in their direct operations and extended supply chains are not charged fees or costs connected to recruitment.

- Companies should maintain effective grievance mechanisms through which workers can seek redress for issues encountered during recruitment.

- Companies should use their leverage to support and promote a global prohibition on recruitment fees and costs charged to workers.

For the Recruitment Industry:

- Recruitment agencies should ensure and promote professional practice and the responsible recruitment of workers.

- Recruitment Industry Associations should promote and help monitor responsible practice in the sector.

Introduction

In 2018, UN member states agreed a common approach to international migration, in all its dimensions, by adopting The Global Compact for Safe Orderly and Regular Migration. The Global Compact foregrounds the need for shared responsibilities, to ensure non-discrimination and respect for human rights, and to promote a cooperative approach to reduce migrants’ vulnerability whilst optimising the benefits of migration to countries of origin and destination.

Opposition to migration continues in many parts of the world. The status of migrant workers, in particular those in low wage employment, remains precarious. This is despite the centrality of migrant workers to effective business operations, as well as the development related benefits of migration to host and destination countries.

As illustrated by the Dhaka Principles for Migration With Dignity, which mark their 10th anniversary in 2022, migrant workers face challenges at all stages of the migration cycle. Much attention has focussed on the deeply flawed processes often in place for the recruitment of low wage migrant workers – including the common practice of charging recruitment costs and fees to workers.

The Employer Pays Principle seeks to address this challenge by affirming that “no worker should pay for a job – the costs of recruitment should be borne not by the worker but by the employer”. Promotion of the Employer Pays Principle by businesses, governments, and civil society organisations is critical to focusing attention on this important issue. Initiatives like the Leadership Group for Responsible Recruitment have been established to address supply chain challenges relating to flawed recruitment practices and to strengthen joint leverage in advocating for policies and practices that would better ensure protection of migrant workers’ rights.

The links between exploitative recruitment practices, debt bondage, and vulnerability to exploitation, including forced labour and trafficking, are well documented. Less acknowledged but of significant importance to governments’ broader policy objectives are the adverse impacts recruitment fees charged to workers have on development outcomes. Servicing recruitment debt seriously erodes the benefits of working abroad for workers, their families, and home and host countries.

Vital revenue that could be used to further a range of options for migrant workers is directed away from workers and instead into the hands of formal and informal recruitment intermediaries, as well as corrupt officials delivering government mandated services and hiring managers in countries of destination.

In addition to the erosion of financial benefits, flawed recruitment may also impede the transfer of human and social capital. Migrant workers who face realities of low wages and indebtedness will not be so easily able to leverage opportunities to acquire new skills or training, nor be able to broaden the social and cultural horizons employment abroad may offer. These financial and social deficits are significant impediments to the realisation of a range of positive development outcomes linked to the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

For those seeking to effect change in the way migrant workers are recruited, lost development potential due to the prevalence of flawed recruitment models can therefore add further compelling arguments for why change to current practices are so urgently needed and can provide additional incentives to do so.

This paper highlights some of the key findings of a research study on flawed recruitment models commissioned by IHRB in 2021 and provides recommendations for further action by different stakeholders involved. It looks at a select number of recruitment corridors that have been identified by members of the Leadership Group for Responsible Recruitment as being of particular importance. The concluding section highlights the importance of moving beyond advocacy around recruitment that focusses solely on preventing modern slavery and towards a broader approach that includes attention to the development benefits which would accrue to local communities and countries by the adoption of responsible recruitment practices based on an Employer Pays Model and commitment to protecting the rights of migrant workers.

International Migration and Recruitment

The contribution of international migration to countries of destination

In a global economy, little is undertaken which has not included input from a migrant worker somewhere. For example:

- Large scale recruitment of migrant workers is a significant feature of a number of economies in South East Asia, such as Malaysia, Thailand, and Taiwan. Primary producers, including palm oil and manufacturing facilities such as electronics in these and many other places, owe their economic viability, in very competitive markets, to a steady stream of low-wage workers from abroad.

- The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, Singapore, and Hong Kong are also dependent on foreign workers across a range of sectors where they play a critical role in developing and maintaining physical infrastructure and delivering a range of services.

- Workers from Central America and the Caribbean are similarly employed in the USA and Canada.

Drivers of migration

For many migrant workers, the significant driver for migration is the chance of a job, any job, and the opportunity to earn money to send back to families and communities at home. Migrant workers engaged in low wage employment are often from the least economically developed countries. In some cases, significant populations still exist close to poverty levels. Unemployment, under-employment, or low wages mean few options for a decent livelihood are available to vast numbers of workers.

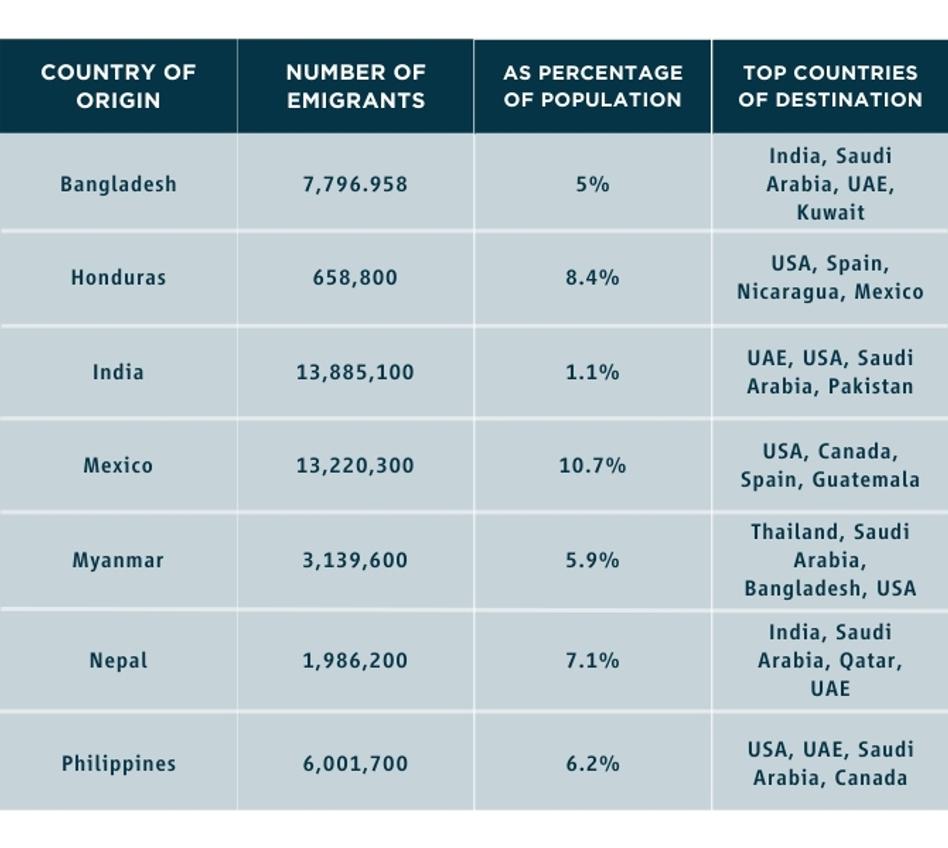

The importance of migration for work in certain countries of origin is illustrated in the table below.

It should be noted that this table only shows those migrating for work as a percentage of the total population in 2020. The percentage of the working population seeking employment abroad is far higher.

Migration for work may also serve to maintain social cohesion and alleviate labour market tensions where unemployment and underemployment serve as a constant backdrop to home economies.

Migration has proven to be an essential driver of development in origin countries, through financial remittances, human capital, and social transfers. As such, achieving “orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration” is recognised in target 10.7 in the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and one which can significantly contribute to the attainment of overarching goals such as inequality reduction, poverty and hunger eradication, improved health, and education.

Flawed Recruitment Process

Despite the significant economic, political, and social advantages of migration for work, migrant workers continue to face challenges at all stages of the migration cycle.

Migrants from developing countries working abroad in low wage jobs, without effective trade unions and other worker-support networks inevitably lack leverage to improve their conditions and are particularly vulnerable to denial of rights and exploitation.

Women migrant workers, 41% of the total migrant workforce, face additional challenges. As noted by the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific Regional Review of Implementation of the Global Compact for Safe Orderly and Regular Migration:

“Although countries in the region have made advances with regard to gender equality and the empowerment of women, women and girl migrants still face limited opportunities and a greater risk of discrimination, exploitation and abuse. “

Migrants may be subject to a variety of exploitations during recruitment such as passport retention or contract substitution, but payment of recruitment fees, costs and charges to secure employment abroad has become a totemic issue attracting considerable attention. The practice of migrants paying these costs is deeply embedded and entrenched within some recruitment corridors. Workers with few employment options in their home countries and lacking accurate knowledge and information about jobs abroad become dependent on a range of licensed and unlicensed recruitment agents and other intermediaries seeking to charge them for the chance of a job abroad.

The role of recruitment agents

Many recruiters’ operating procedures fail to align with international standards, and business models are based on exploitation of workers. An oversupply of recruitment agencies and other intermediaries, combined with large numbers of potential migrants desperate for a job abroad, mean intense competition amongst the agencies and lack of leverage with hiring managers abroad.

In some situations, hiring managers or recruiters in countries of destination will expect payments for job offers to be made, effectively selling jobs. Recruiters in countries of origin will inevitably add these costs to the fees they are charging workers. Over the years, this system has become deeply entrenched and is often viewed as perfectly normal, including by workers, who may even be suspicious of ethical agencies who operate without charging fees.

The costs charged to workers often go far beyond the genuine costs of recruitment and deployment. Sums of several thousand dollars which may amount to many months salary, are not uncommon. As well as being additional burdens for workers this may impact businesses who do not necessarily end up with the best worker for specific jobs but instead those prepared to pay the highest fees to secure the position.

In some countries of origin, the recruitment sector is poorly served by national associations who may fail to promote international standards or adherence to even their own codes of conduct. Membership to some associations is automatic on being granted a recruitment agency licence meaning little market incentive exists to deliver good service to members.

When such systems predominate, with those who charge fees to workers able to offer low or no cost supply of labour to businesses abroad, responsible recruitment agencies who charge fees to businesses instead are often disadvantaged and unable to compete.

Grievance mechanisms

Migrant workers may lack access to effective grievance mechanisms to address abuses from recruitment. In cases where such mechanisms exist, they may be inadequate for securing some form of remedy (usually reimbursement of fees) to compensate for harms linked to their recruitment. The practice of companies reimbursing fees, if it is found that workers have paid them, has received increasing attention in recent years. Private sector consultancy Impactt developed a set of Standards for Repayment based on their experience of helping organise repayment schemes to workers for their employment in the Gulf and SE Asia. Although actions by companies to reimburse workers is a reflection on the lack of effective due diligence over recruitment processes, such repayments should at least remove the worst debts for workers. The hope is that having paid once, and often having borne costs far higher than those that would have been paid had the workers been recruited ethically, companies will in future ensure more effective oversight of their recruitment arrangements.

Responsible Recruitment and Development

Many efforts to prevent fee charging to workers have been set within a “modern slavery” paradigm. A growing number of businesses have included this issue as being of critical concern to their operations. For example, The Consumer Goods Forum’s Priority Industry Principles to Prevent Forced Labour stipulate that “no worker should pay for a job”.

Governments too have referenced this principle in a variety of joint action plans to combat forced labour. Recent “Withhold Release Orders” enacted by the US Government have impounded goods at the US Border when produced by migrant workers subject to recruitment debt until repayment plans to reimburse workers have been enacted. Although prevention of forced labour is a critical issue, it does not address the root causes of current practices and their implications in perpetuating the vulnerability of migrants to exploitation.

Of significant importance to broader policy and advocacy efforts is the adverse impact recruitment fees charged to workers have on the socio-economic development of countries and communities. Servicing recruitment debt seriously erodes the benefits of working abroad – for workers, their families, and countries of origin and destination.

Vital revenue that could be used to improve livelihood opportunities, is directed away from workers and their families. Instead, it often falls into the hands of formal and informal recruitment intermediaries, as well as corrupt officials delivering government mandated services and hiring managers in countries of destination.

As well as the erosion of financial benefits, flawed recruitment may also impede the transfer of human and social capital. Migrant workers who face realities of low wages and indebtedness will not be so easily able to leverage opportunities to acquire new skills or training, nor be able to broaden the social and cultural horizons employment abroad may offer. These financial and social deficits are significant impediments to the realisation of a range of positive development outcomes linked to the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Economic remittances

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and associated Sustainable Development Goals adopted by all UN Member States in 2015 provide a blueprint for action on a range of targets to reduce poverty and inequality, protect health and wellbeing whilst safeguarding the planet. Protection for migrants is acknowledged in SDG 10.7:

“Facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people, including through the implementation of planned and well-managed migration policies”

Migrant remittances, often being sent to some of the most financially challenged countries and communities, have the potential to help deliver a range of development benefits. In 2021, total remittances to low- and middle-income countries was expected to total $589 billion – 3 times the amount received in Official Development Assistance (ODA).

Remittances may be regular or intermittent, the transfer taking place through formal or informal channels. The cost of formal remittance transfers has also been the subject of scrutiny. The impact of transaction costs are acknowledged by SDG 10c which states:

“By 2030, reduce to less than 3 percent the transaction costs of migrant remittances and eliminate remittance corridors with costs higher than 5 percent.”

In March 2021 however , The World Bank Remittance Quarterly found an average of 6.31% in formal transaction costs. High transaction charges may encourage workers to favour informal channels which can increase financial risk and may inhibit financial management that maximises the gains from employment abroad such as regular saving.

Women migrant workers remit significant proportions of the money they earn abroad. A 2017 report by UN Women noted that “Though their wages are typically lower, women migrants are likely to send home a higher proportion of their earnings more frequently.” Furthermore, “the remittances of women migrant workers are more likely to be spent on health, education and family development”. The report also notes, however, that women “may not retain control over remittance spending once funds are transferred home. Restrictive laws and practices governing women’s control over property can limit their ability to acquire assets in their home countries”. Better acknowledgement of women migrant workers’ significant contribution to both economies at home and the global economy should therefore be an important component of any strategy focused on migration for work. Governments should prioritise legislative measures to guarantee equal opportunities and pay, ensure women’s access to financial services, and support training in financial management.

For many countries of origin, remittances represent a significant share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In Nepal for example, remittances represented over a quarter of GDP and five times as much received in Official Development Assistance (ODA). It should also be remembered that this portion of GDP is delivered to some of the most economically challenged communities in countries of origin. The ability of migrants to remit money regularly is also dependent on their access to wages paid directly to them, in full, and on time.

Remittance Inflows to Countries of Origin (2020)

Social Remittances

The contributions and gains made by migrant workers and their impact on countries of destination and origin are not only economic. Work abroad may also bring other benefits in acquisition of new skills, competencies, and ideas. Exposure to different countries, cultures, and job sectors may help individual migrants develop ideas and ways of thinking that could be of immense benefit either whilst abroad or at home.

Some former migrants will go on to undertake further education, start new business ventures, or contribute to their communities in other ways. Women migrant workers may benefit from enhanced status due to the money they have earned abroad and be more ready to assert their rights after time away from sheltered, patriarchal families and communities.

These positive social impacts may, however, be difficult to achieve in situations where flawed recruitment practices and associated vulnerability to exploitation exist. As Desiderio notes:

“Equally worrisome - although difficult to quantify - is the loss of social remittances and human capital returns due to migrant indebtedness. Migrant workers compelled to work overtime to survive while repaying debts may not be able to participate in workplace training, including finance training when this is on offer. They are also less likely to actively join diaspora organisations, which offer crucial support both to individual wellbeing and the development agency of their members. In general, migrants experiencing various forms of labour exploitation cannot afford expanding their human and social capital while in their countries of destination, thus losing out on key levers of human development and broader development contributions from migration. The predominant young age of migrant workers – and returnees - exacerbates the negative consequences of this lost opportunity for migrant themselves, their origin communities and countries, as well as their receiving countries.”

Furthermore, returning after time working abroad is not always a positive experience. Former migrants may find it difficult to reintegrate into their communities. Workers may find it hard to return to low wage manual work at rates below those paid abroad or find opportunities to utilise the new skills they have gained.

As noted in a briefing by UN Women:

“Women migrant workers may not retain control over remittance spending once funds are transferred home. Restrictive laws and practices governing women’s access to and control of property can limit their ability to acquire assets in their home countries… Some women may face stigma for their time away from home or not wish to reintegrate into underdeveloped often rural patriarchal societies.”

The challenges of reintegration for both men and women returnee migrant workers are explored more fully in a number of reports on the IOM Return and Reintegration Platform make clear the need for Government supported programmes and reintegration strategies, and effective support structures for returning migrants that could help fully maximise savings, skills and experience gained abroad; a difficult ask in countries where provision of even basic services may be limited.

Finally, on return, some workers may still carry the recruitment debts from their migration; now finding themselves no better off or even in a situation of negative equity.

Government Processes

Countries at both ends of the recruitment corridor keen to maintain high levels of migration and its associated benefits should see advantage in protecting migrant workers during recruitment.

For countries of destination flawed recruitment processes that exploit workers may lead to inefficiencies and contribute to poor productivity. They may also bring additional international scrutiny and economic or other sanctions. For countries of origin it can make it citizens vulnerable to exploitation and reduce the amount of money remitted from abroad. Lack of effective oversight and regulation of recruiters may mean that tax revenues are not being collected effectively from the industry. Poorly designed, expensive and bureaucratic migration processes can also become places where fees may be extracted or provide other opportunities for corruption and bribery.

Recruitment costs are also likely to result in a movement of money earned by those recruited to work abroad away from the most impoverished rural areas to the towns and cities where recruitment agencies and their intermediaries are located. A considerable proportion of the benefits of working abroad therefore accrues to urban centres and not to the rural villages where enhanced development outcomes might be most needed.

The other significant transfer of money, ironically, may be back to countries of destination. Recruitment agencies in countries of origin are often expected to pay kickback payments or bribes to hiring managers or other recruitment intermediaries in countries of destination. Jobs abroad are thus effectively sold to those prepared to pay the most – these costs will ultimately be passed on to migrant workers. This suggests that the contributions from remittances to countries of origin may be considerably less than headline GDP figures, with money earned abroad arriving home only to return to where it came.

It is worth noting, however, that in international labour markets, the prohibition of worker-paid recruitment fees may make labour sourcing from certain countries uncompetitive. Origin country governments may lack leverage to make demands of authorities in countries of destination, meaning protections for their citizens may be a low priority in bilateral agreements.

Cooperation amongst countries of origin and destination is clearly needed. The Abu Dhabi Dialogue, a consultation process between countries of origin in Asia and destination countries in the Gulf, is an example of such engagement but remains unique and still sees the majority of workers travelling to the Gulf paying recruitment charges.

In 2020, The Montreal Recommendations on Recruitment, a process organised by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), sought to offer a roadmap for better regulation of the recruitment industry, bringing together licensing and enforcement bodies from countries around the world.

The Montreal Recommendations offer policymakers and regulators practical guidance and ideas to improve regulation and oversight of international recruitment and protection of migrant workers including on:

- recruitment fees;

- licensing and registration of labour recruiters;

- inspections and enforcement;

- access to grievance mechanisms and dispute resolution;

- bilateral and multilateral mechanisms;

- migrant welfare and assistance.

Further development and promotion of the recommendations is now required if they are to become the global standards for recruitment regulation.

Government processes may also fail to adequately address the additional challenges women may encounter in migrating for work. Women may face restricted opportunities or be channelled into particular occupations. Several countries such as Bangladesh have sought to “protect“ women from being exploited through bans on their emigration to particular countries or sectors, with the result that many still continue to travel abroad but through irregular channels with even less protection.

Effective legislation and enforcement are needed to better protect workers migrating through many recruitment corridors. Such measures would not just protect individual migrant workers but also allow rights respecting business, both recruiters and those employing migrant workers to compete fairly within the law.

Conclusions and Recommendations

There are 169 million migrant workers in the world meaning 1 in 20 workers is a migrant. This paper has highlighted their importance to both counties of origin and destination. Demographic changes, notably aging populations and falling birth-rates in richer countries, will require younger migrant workforces to maintain them. Threats such as the climate crisis will see increased numbers of workers on the move. There is an urgent need for more effective government action at all levels, to manage migration for work; with proper accountability and support from business, trade unions, and civil society.

Ensuring migrant workers are not subject to exploitative recruitment practices will not only contribute to realisation of fundamental rights, but also enable a range of other positive outcomes for countries of both destination and origin. Improving recruitment practices and implementing a global prohibition on workers being charged recruitment fees aligns with international standards and human rights commitments and is an important contribution to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

The UN Global Compact for Safe Orderly and Regular Migration presents a significant opportunity to address the challenges associated with migration for work, to improve the governance of migration, and to strengthen the contributions of migrants to sustainable development. This paper has focussed in particular on GCM Principle 6 - Facilitate fair and ethical recruitment and safeguard conditions that ensure decent work. Adoption of models of recruitment that prohibit the charging of recruitment fees to migrant workers – The Employer Pays Principle – would better protect all workers, provide a level playing field for law-respecting businesses, and foster better outcomes for developing economies.

Recommendations for Governments (Origin and Destination)

1. Governments should ensure clear transparent and accessible processes for international recruitment.

- Governments should align their recruitment policies for both inward and outward migration with the ILO General Principles and Operational Guidelines for Fair Recruitment.

- Governments should prohibit the charging of recruitment fees and related costs to workers in accordance with the ILO Definition of Recruitment Fees and Related Costs.

- Employers and recruitment agencies found to have charged fees to workers should be obliged to make repayment in full.

2. Governments should develop robust, transparent, and publicly accountable licensing systems for recruitment agencies.

- Governments should ratify ILO Private Employment Agencies Convention 181.

- Effective licensing or oversight mechanisms to manage the activities of recruitment intermediaries should be established such as the Gangmaster and Labour Abuse Authority Licensing Scheme in Great Britain.

- Recruitment agencies should be required to operate to globally recognised international codes of conduct such as The World Employment Agency (WEC) Code of Conduct.

3. Bilateral agreements between governments should include clear and binding prohibitions on charging recruitment fees to workers in both countries of origin and destination.

- Governments should invite ILO experts, worker organisations and civil society to provide input into these negotiations and design of these arrangements.

- Governments should ensure that consular staff and labour attaches are aware of legislation and processes relating to the recruitment of migrant workers through the relevant corridors.

- Governments from destination countries should establish consular support and visa processing centres for potential migrant workers in their countries of origin such as those operated by the Government of Qatar in a number of South Asian countries and by the USA in Mexico.

- Governments in destination countries should ensure parity in pay for women workers and that migrant workers receive the same pay and conditions as national workers.

- Governments should ensure women’s access to financial services.

Recommendations for Business

1. Companies should commit to the Employer Pays Principle and ensure that workers in their direct operations and extended supply chains are not charged any fees costs or charges connected to recruitment.

- Company codes of conduct for recruitment should include clear responsible recruitment processes.

- Contracts and service level agreements with suppliers should stipulate that recruitment fees should not be charged to workers.

- Recruitment processes should be included in all internal audits and those of suppliers.

- Companies should map and have a good understanding of where workers being used in their supply chains are coming from and undertake enhanced due diligence if risk of exploitation during recruitment is high.

2. Companies should ensure effective grievance mechanisms for workers through which they can include issues relating to recruitment.

- Where evidence of fees being charged to workers is revealed, companies should immediately seek to reimburse those fees to the workers.

3. Companies should use their leverage to promote and support a global prohibition on recruitment fees to workers.

- Companies should support and join multi-stakeholder initiatives focused on strengthening responsible recruitment practices.

- Companies should advocate for responsible recruitment within existing business organisations and seek to see responsible recruitment reflected in membership criteria and codes of conduct.

- Companies should advocate with governments to promote greater protections for migrant workers and law-abiding business relating to recruitment practices enshrined in law supported by effective enforcement activities.

Recommendations for the Recruitment Industry

1. Recruitment agencies should ensure and promote professional practice and the responsible recruitment of migrant workers at all times.

- Recruitment agencies should not make any charges to workers for recruitment but instead contract with the end user business for their services.

2. Recruitment Industry Associations should promote responsible recruitment practice.

- Business associations representing recruitment agencies should recognise and respect ILO Private Employment Agencies Convention 181 and prohibit fee charging by their members.

- Business associations representing recruitment agencies should develop clear professional codes of conduct such as the World Employment Confederation Code of Conduct and ensure their members adhere to them.

- Recruitment agency associations should have market incentives to encourage delivery of high standards of professional services to their members. Membership of an association should not be automatic on the award of a recruitment agency licence.

Download the full report

Acknowledgments

Federal Department of Foreign Affairs FDFA, Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation SDC.

Attribution

This work is the product of the Institute for Human Rights and Business (www.ihrb.org). It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. You are free to copy and redistribute this work in any medium or format for any purpose, even commercially, provided that you give credit to IHRB and indicate if any changes were made to the original content. © 2022 IHRB