Over the past few years, respect for human rights has taken center stage on the corporate responsibility agenda. It is a development which has been animated and accelerated by the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (Guiding Principles), the globally authoritative standard for corporate human rights responsibilities. But while the Guiding Principles are the source of conceptual clarity, in their wake lie myriad challenges for practical implementation. These challenges are arguably most complex in the realm of supply chain management[2], a crucial frontier in the drive to ensure businesses respect human rights and the source of increasing legal risk.[3]

Structured Prioritization of Human Rights Risks

Recognizing the scale of the challenge, the UN Global Compact recently published a Good Practice Note entitled A Structured Process to Prioritize Supply Chain Human Rights Risks. Good Practice Notes (GPNs) aim to provide practical guidance to businesses regarding how to manage complex sustainability challenges. Rather than focusing on specific case studies, GPNs seek to identify general approaches that have been recognized as effective by companies and stakeholders. Each GPN is developed under the aegis of a specific working group, comprised of representatives from business and civil society.

The new GPN was researched and written by Enodo Rights at the request, and under the supervision, of two working groups: the Supply Chain Working Group and the Human Rights and Labour Working Group. We benefited from the invaluable insight of a range of experts from business, civil society and international organizations. We chose this focus based on our interviews with leading sustainable businesses: even the best-intentioned companies fall into the trap of identifying supply chain human rights priorities based on untested assumptions about “relevant” rights and “plausible” involvement links—to the detriment of the company and its stakeholders.

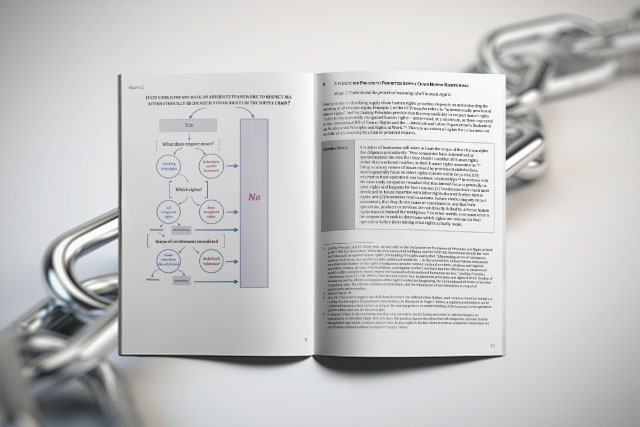

The challenge companies face is to translate what the Guiding Principles say about the scope of business responsibility to respect rights into a practical decision-making process. Our Note proposes one structured process to identify the right supply chain human rights priorities. It is driven by a structured impact assessment that identifies supply chain human rights impacts precisely so that companies can respond appropriately. The prioritization process thus has three broad stages:

-

Understand the practical meaning of all recognized human rights: The Guiding Principles provide that business responsibility for human rights applies to all internationally recognized human rights. These include, at a minimum, the International Bill of Rights and the International Labor Organization’s Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. An understanding of all these rights, and what they mean for business, is the cornerstone of an effective human rights program in general, and prioritization in particular.

-

Conduct impact assessment using meaning of rights and types of “involvement”: Once a business understands the meaning of all human rights it is in a position to conduct a structured impact assessment. The assessment should seek to identify the particular adverse human rights impacts with which the company is actually or potentially involved. Businesses are expected to (a) address adverse impacts that they cause or contribute to and (b) seek to mitigate or prevent those that are “directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships, even if they have not contributed to those impacts.”[4] A company should seek to obtain as complete a picture as possible of its suppliers as part of the impact assessment; however, where it is infeasible to conduct due diligence across the entire supply chain, companies should prioritize first the areas of the supply chain where the risks of adverse human rights impacts are most significant.

-

Prioritize response based on severity of rights impact: Effective prioritization turns on these prior two stages. In theory, prioritization is only necessary where a company is unable to address every one of its adverse human rights impacts simultaneously.[5] In practice, prioritization of responses will often be essential for companies with extensive supply chains. This prioritization is independent of the involvement link between the business and the impact. Rather, prioritization of responses should be driven exclusively by the severity of the rights impact on stakeholders, which turns on “scale, scope and irremediable character”—regardless of how the business is involved with the impact.[6] This prioritization must be the product of due diligence, not the driver of it.

Conclusion

Prioritizing human rights risks, particularly in the supply chain, is a business imperative for many companies. But an ad hoc approach serves neither the company nor its stakeholders. Progressively narrowing focus through the impact assessment can result in a process that is both practical and principled. Companies could then be assured that they had identified the right priorities in a way that they could effectively explain to stakeholders, courts, governments and investors.

A Structured Process to Prioritize Supply Chain Human Rights Risks details this structured approach with examples of good practice from businesses across sectors.

[1] Enodo Rights is a business and human rights consulting firm that blends legal expertise and stakeholder engagement experience to design corporate human rights strategy. Enodo advises companies across sectors on the legal implications of the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, structured human rights due diligence, innovative stakeholder engagement, and effective system design. Further information and publications are available at enodorights.com.

[2] Supply chain management is the process of systemically optimizing the corporate supply chain to meet the company’s primary goals, with a view to improving the company’s performance as well as that of entities within the supply chain.

[3] Class-action lawsuits recently launched in the US against Nestlé, Costco, Walmart and JC Penney bring these risks into stark relief. Canadian companies, notably Loblaws, find themselves similarly exposed.

[4] Guiding Principles, II.A.13.

[5] Guiding Principles, Commentary to II.A.24 (“While business enterprises should address all their adverse human rights impacts, it may not always be possible to address them simultaneously. In the absence of specific legal guidance, if prioritization is necessary business enterprises should begin with those human rights impacts that would be most severe, recognizing that a delayed response may affect remediability.”

[6] Guiding Principles, Commentary to A.II.14 (“Severity of impacts will be judged by their scale, scope and irremediable character.”).

The perception of ‘value’ needs to change if the World Bank’s mission is to succeed

Last week we attended the Spring Meetings of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) in Washington, D.C. The annual IMF-World Bank meetings bring together finance ministers and central bankers from all regions as a platform for official...

26 April 2024 | Commentary

Commentary by Vasuki Shastry, Author, ESG/Strategic Communications Expert; International Advisory Council, IHRB Haley St. Dennis, Head of Just Transitions, IHRB