This year’s Global Forum for Responsible Recruitment took stock of ongoing efforts to protect the rights of migrant workers around the world through more effective regulations and corporate practices, including strategies to eradicate worker-paid recruitment fees. I was pleased to moderate a Forum session that looked at one critical dimension often overlooked in migration related discussions - the vital role played by women workers, including in the technology sector, and the many vulnerabilities they face in their migration journeys.

Moving migrant women workers to the centre of responsible recruitment strategies:

The roles of tech firms in promoting progress

When we think about women who migrate for work within global supply chains, certain types of labour are often front of mind - perhaps in a garment factory, a farm, or in a private home. Rarely are other sectors like tech considered, nor are the challenges faced of how these workers arrived at the point of destination or how they may return home. This incomplete perspective not only fails to capture the complexities of the migration experience, but also leads to disjointed policies and programming, leaving women further exposed to multiple risks of exploitation.

Addressing these shortcomings requires information, dialogue and a commitment to joint action. When it comes to understanding the issues, consider for example, that women are more likely than men to be subjected to physical and sexual violence and threats against family members (IOM 2022), and yet a specific approach targeting women’s differentiated needs linked to the world of work is often left out of responsible recruitment strategies.

Greater attention to the distinct stages of labour migration can help structure a deeper understanding of the risks women face and can assist in the development of more effective strategies to support women migrant workers. These three stages are seen in

-

(1) recruitment and transit, as women are more likely to take irregular and more dangerous migration routes subject to higher rates of fraud and human rights violations, such as human trafficking, sexual assault, and physical violence.

-

(2) on the work site, as women are disproportionately affected, for example, by sexual harassment and pregnancy discrimination, wage inequity and lack of wage transparency; women are more likely to be coerced through wage non-payment and abuse of power.

-

(3) the return home, as women face stigma and rejection (perhaps suspected of misconduct while abroad) which can lead to social isolation, family estrangement, and mental health issues due to shame and trauma.

Global brands, suppliers, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), researchers and investors can do more to put migrant women at the centre for responsible recruitment strategies. Incorporating migrant women’s differentiated needs in responsible recruitment will have compounding benefits, for example: (1) women migrants will have safer migration journeys and greater wellbeing in the workplace; (2) suppliers will likely have less turnover and workers that report higher rates of wellbeing; and (3) brands will be better positioned to reach their responsible recruitment goals, likely with greater speed and transparency.

How can better data help inform protections and opportunities for migrant women?

There is limited country-, corridor-, and commodity-specific data on the challenges women migrants face. This lack of information impacts the depth of insight into issues such as women’s training needs at community of origin (e.g., financial literacy and worker’s rights laws in country of destination) or comparative rates of women who experience modern slavery and exploitation indicators. It also means less awareness of the amount of fees paid by women during recruitment, and unintended consequences, for example of protectionist policies meant to help women. If responsible recruitment strategies and related fair work standards incorporated deep gender analysis, we’d have more insights to inform programmes that directly counter vulnerabilities faced by women in migration and labour force participation. Consistent, reliable data would offer companies and suppliers the ability to better diagnose gaps, target their programming to women’s needs, and achieve gender-smart goals.

What could the future look like for migrant women?

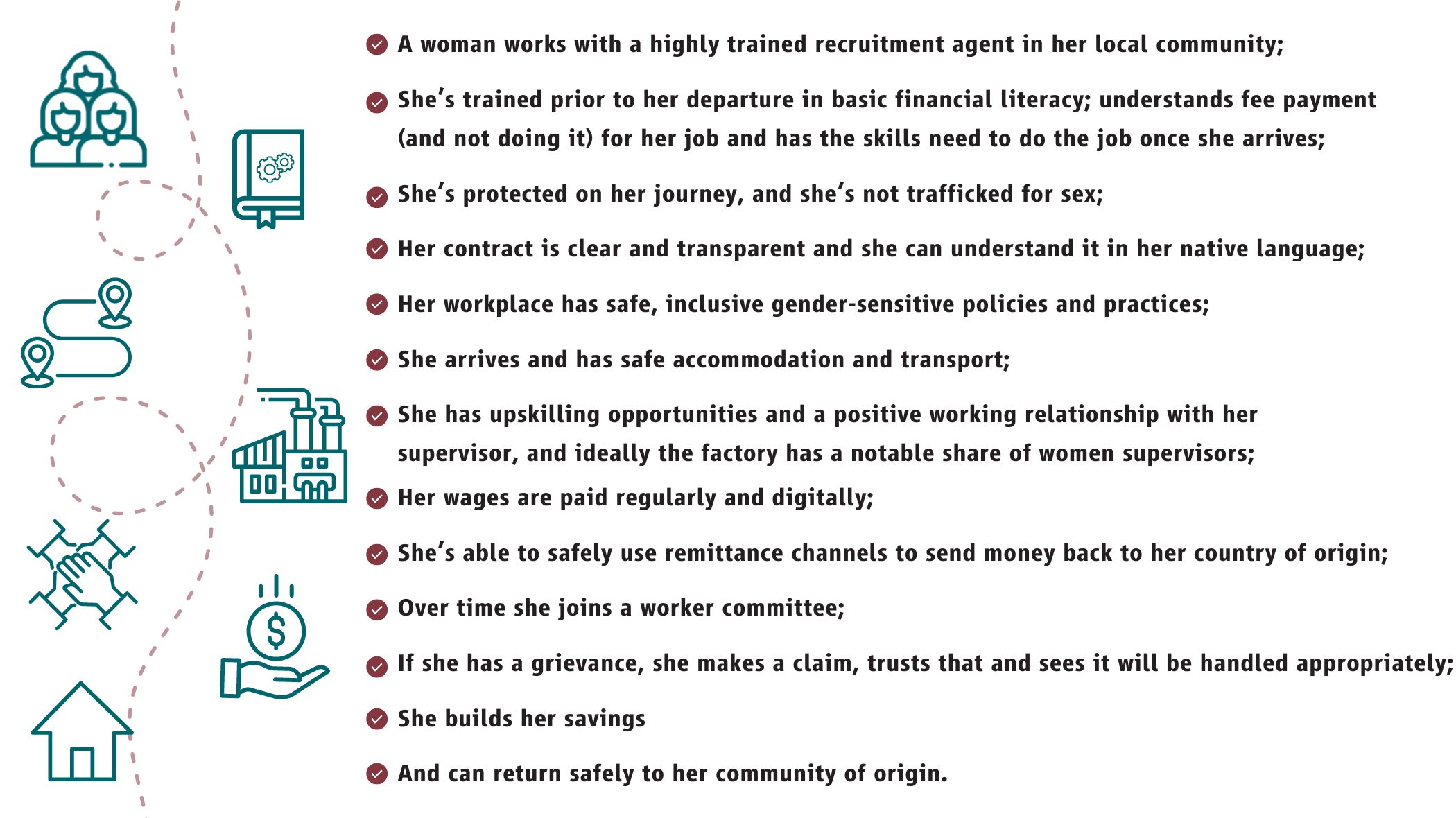

Using the Dhaka Principles for Migration with Dignity as a template for safe labour migration, treatment of workers can and should be inclusive of women and their rights. This means that from recruitment to returning home, a woman has been treated with dignity and respect. A woman’s migration journey could meet the spirit of the Dhaka Principles if the following were true, for example:

What role can tech companies play in supporting migrant women in creating a Dhaka Principles-aligned reality?

The ideal scenario outlined above is a True North that will require significant policy and programmatic shifts in global supply chains. Insights and information from challenges faced by the garment industry and the lived experience of garment women workers during their migration journeys should be fully harnessed in order to move in this direction. At present, there is little public information into the women who work within other industries like electronics and on how their migration experiences may differ from other sectors. While women predominate apparel frontlines, women can be more easily outnumbered in tech factories which can make them even more at risk to abusive power dynamics from male supervisors. For example, there are very few case studies written about women in electronics factories, and very little research or data undertaken within the industry.

In the time ahead, there is an urgent need to focus more on what should be done to address women electronics workers’ unique challenges as companies try to recruit more responsibly. Our discussion during the Global Forum was a helpful deep dive into the role of the tech sector in promoting gender equity in responsible recruitment, with a specific focus on electronics factories in Taiwan. It highlighted the need for more gender data and case studies from the electronics sector for insights into

-

Women’s overlapping vulnerabilities in lower tiers in global supply chains where electronics component parts are made before reaching tier 1 suppliers. It also stressed the importance of more effective guidance for brands to enter spaces where both their leverage and risk is greatest, as well as better training for brand staff internally. Finally, the discussion made clear that

-

Bringing rights holders’ perspectives more directly into ongoing planning and practices is a critical step, as is improving legal protections and awareness of available remedies before recruitment.

These are all significant challenges to be addressed, but the Forum, and the community of committed actors working to make responsible recruitment and migration with dignity a reality offers some hope for a better future.

The perception of ‘value’ needs to change if the World Bank’s mission is to succeed

Last week we attended the Spring Meetings of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) in Washington, D.C. The annual IMF-World Bank meetings bring together finance ministers and central bankers from all regions as a platform for official...

26 April 2024 | Commentary

Commentary by Vasuki Shastry, Author, ESG/Strategic Communications Expert; International Advisory Council, IHRB Haley St. Dennis, Head of Just Transitions, IHRB